Produce personalized presentation boards that distill complex concepts into simple visual representations with a few helpful tools and effects.

Articles

How to Create Architectural Presentation Boards

Unified Architectural Theory: Chapter 4

We will be publishing Nikos Salingaros’ book, Unified Architectural Theory, in a series of installments, making it digitally, freely available for students and architects around the world. The following chapter discusses the complexity of form languages and describes how to use the form language checklist to measure these complexities. If you missed them, make sure to read the introduction, Chapter One, Chapters 2A and Chapter 2B, and Chapter 3 first.

There exists a volume of writings by architects in the early 20th century, and we can look through them for the form languages of Modernism. Unfortunately, the useful material turns out to be very little, most of it describing not a form language but rather marketing and declarations of a political nature. Moreover, those pieces of very personal form languages are presented as normative theories: a prescription of what to do and what not to do, with the weight of universal ethics, even though they are based solely on opinion, not empirical observations or systematic study.

Here are some practical lists of rules I have found by Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier.

Happy Cities and Stranger Danger: An Interview with DIALOG's Bruce Haden

In this article, first published by Indochino as “What makes some buildings happy?” architect Bruce Haden, principal at DIALOG in Vancouver, discusses why some places feel good to be in and why some just have that awkward, quiet feeling.

Award-winning architect and urban planner. Dad. Researcher on happy vs. lonely cities. We talked to Bruce Haden about why some places feel good to be in, and some just have that awwwkward, quiet feeling.

Bruce Haden has only been an architect and a bartender. So ask him what he likes about it, and his answer is he doesn’t really know anything else. In high school, he didn’t want to pick between calculus and woodshop, so he ended up in a profession that’s part art, part engineering (and a fair amount of politics). Now, he works on a lot of large, public buildings. But he also spends a lot of time thinking about happy and lonely cities. He talks about how working with a client is like dating, why some buildings are worth being in and others are just empty, and whether adventure or luxury wins.

Six "Miracle" Materials That Will Change Their Industries

The following six "miracle" materials could be headed straight into your home, office, car and more. Dina Spector at Business Insider recently rounded up the six most promising materials. As of now, their potential applications have just scratched the surface, but the possibilities are endless. Presented by AD Materials.

Scientists are constantly on the look out for lighter, stronger, and more energy-efficient materials. Here's a glance at some materials that will change the way we build things in the future.

Architecture for Humanity Toronto Launches Lecture Series: "Incremental Strategies for Vertical Neighborhoods"

According to the most recent national census in Canada, almost half of Toronto residents are immigrants, one-third of whom arrived in the past ten years. To allow the city to adapt to this surging flow of immigrants, Architecture for Humanity Toronto (AFHTO) has called upon students and professionals from various backgrounds to rethink Toronto's urban fabric - and, in particular, its high-rise developments - by establishing a series of lectures and workshops entitled "Incremental Strategies for Vertical Neighborhoods."

At the inaugural event a few weeks ago, Filipe Balestra of Urban Nouveau* was invited to speak about his work and contribute to a design charrette inspired by the City of Toronto's Tower Renewal program. For more on Balestra and the event, keep reading after the break.

The Hudson Yards - New Development, "Smart" Development

The largest private project New York City has seen in over 100 years may also be the smartest. In a recent article on Engadget, Joseph Volpe explores the resilience of high-tech ideas such as clean energy and power during Sandy-style storms. With construction on the platform started, the Culture Shed awaiting approval, and Thomas Heatherwick designing a 75-Million dollar art piece and park – the private project is making incredible headway. But with the technology rapidly evolving, how do investors know the technology won't become obsolete before its even built?

A Delicate Endeavor: The Restoration of Modern Masterpieces by Schindler, Lautner, and The Eameses

How do you make a space more livable by current standards, while simultaneously upholding the original architect's design intentions? It's a delicate endeavor, but one that was recently accomplished by a couple of architects in Southern California. Originally published by AIArchitect as "Pacific Coast Sun Rises on Modernist House Restorations," this article investigates the thoughtful restorations of three homes designed by the pioneering modernists Rudolph Schindler, John Lautner, and Charles and Ray Eames.

Los Angeles’ early Modernist pioneers are no longer around to oversee the restoration of homes they designed more than a half-century ago, but their landmark projects are offering a new generation of designers historic case studies in Modernist preservation that grow more and more significant with each passing day. Vintage architectural renderings and drawings, photos, and notes are all ingredients these architects use to summon the spirits of Rudolph Schindler, John Lautner, and Charles and Ray Eames, to name a few, bringing their early works of California Modernism back to life.

Big Ideas, Small Buildings: Some of Architecture's Best, Tiny Projects

This post was originally published in The Architectural Review as "Size Doesn't Matter: Big Ideas for Small Buildings."

Taschen’s latest volume draws together the architectural underdogs that, despite their minute, whimsical forms, are setting bold new trends for design.

When economies falter and construction halts, what happens to architecture? Rather than indulgent, personal projects, the need for small and perfectly formed spaces is becoming an economic necessity, pushing designers to go further with less. In their new volume Small: Architecture Now!, Taschen have drawn together the teahouses, cabins, saunas and dollhouses that set the trends for the small, sensitive and sustainable, with designers ranging from Pritzker Laureate Shigeru Ban to emerging young practices.

Opinion: Architecture Should Not Cost Lives

.jpg?1400008808&format=webp&width=640&height=580)

Is it more dangerous to be a soldier or a construction worker? Astonishingly, it’s the latter. According to a recent report in the Guardian, 448 British soldiers have been killed in Afghanistan since 2001. In the same period, 760 construction workers died on British building sites.

Life is cheap at the dirty end of architecture and not just in the UK. The number of fatalities of largely migrant workers from the Indian subcontinent imported to implement Qatar’s architectural ambitions, notably the stadiums for the 2022 World Cup, has been the subject of much hand-wringing discussion. And rightly so − over 400 Indian and Nepali building workers died in Qatar in 2013, and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) has warned that up to 4,000 workers may die before a ball is finally kicked in 2022.

If 400 people perished in a plane crash, there would be exhaustive inquiries into aircraft safety, lessons would be learnt and strategies of improvement implemented. There would also be a palpable sense of loss and accountability. But a fatality here and there on a construction site over a period of time does not have the same galvanizing impetus.

Twenty Years Later, What Rural Studio Continues to Teach Us About Good Design

Hale County, Alabama is a place full of architects, and often high profile ones. The likes of Todd Williams and Billie Tsien have ventured there, as have Peter Gluck and Xavier Vendrell, all to converge upon Auburn University’s Rural Studio. Despite the influx of designers, it is a place where an ensemble of all black will mark you as an outsider. I learned this during my year as an Outreach student there, and was reminded recently when I ventured south for the Studio’s 20th Anniversary celebration. While the most recent graduates took the stage, I watched the ceremony from the bed of a pick-up truck, indulging in corn-coated, deep-fried catfish, and reflected on what the organization represents to the architecture world.

Since its founding in 1993 by D.K. Ruth and Samuel Mockbee, the Studio has built more than 150 projects and educated over 600 students. Those first years evoke images of stacked tires coated with concrete and car windshields pinned up like shingles over a modest chapel. In the past two decades, leadership has passed from Mockbee and Ruth to the current director, Andrew Freear, and the palette has evolved to feature more conventional materials, but the Studio remains faithful to its founding principal: all people deserve good design. Now that it is officially a twenty-something, what can Rural Studio teach us about good design?

Trading "Should" for "Could": Opening up Debate on the Obama Library Design

Originally published in Metropolis Magazine as "Possibilities over Prescriptions," this article by Marshall Brown suggests that we open up the conversation to a wider range of possibilities for the Barack Obama Presidential Library. Brown asks "Rather than narrowing the president’s choices based on race, what if the field of candidates could be expanded?"

The official process to build the Barack Obama Presidential Library has finally been launched. After years of gossip and rumors about architects and sites, this could be the moment for some intelligent and informed debate among the design community. Unfortunately, the conversation so far has been dominated by narrow prescriptions about what the library should be, who should design it, and where it should be located, as opposed to broader speculation about what it could be. So I propose that, rather than making prescriptions to the president based on a narrow set of perceived realities, we can help him by expanding the conversation and laying out a broader set of possibilities.

Terunobu Fujimori's Soft-Hard Zinc House Opens Near Tokyo

A new private house designed by an exceptional Japanese architect, Terunobu Fujimori, has opened. The new building is located in a small provincial town near to Tokyo. Neighbored by typical one-family residences, the newcomer comes to the fore. Different, shiny and apparently soft metallic façade catches the visitor’s eye.

Yet the scale of the building is much smaller than one might expect. Every height, width and depth are accurately measured and left from a certain point of view spatially stingy: no waste is admissible here.

O+A: In Search of Optimal Office Design

Although office design has dramatically and drastically changed over the course of the 20th century, we aren't finished yet. San Francisco firm O+A is actively searching for today's optimal office design, designing work spaces to encourage both concentration and collaboration by merging elements from the cubicle-style office with those popularized by Steve Jobs. In this article, originally published by Metropolis Magazine as “Noises Off,” Eva Hagberg takes a look at some of their built works.

In the beginning was the cubicle. And the cubicle was almost everywhere, and the cubicle held almost everyone, and it was good. Then there was the backlash, and the cubicle was destroyed, put aside, swept away in favor of the open plan, the endless span of space, floor, and ceiling—punctuated by the occasional column so that the roof wouldn’t collapse onto the floor plate—and everyone talked about collaboration, togetherness, synergy, randomness and happenstance. Renzo Piano designed a New York Times building with open stairways so writers and editors could (would have to) run into one another, and everyone remembered the always-ahead-of-the-curve Steve Jobs who, when he was running Pixar, asked for only two bathrooms in the whole Emeryville building, and insisted they be put on the ground floor lobby so that designers and renderers could (would have to) run into each other, and such was the office culture of the new millennium.

And then there was the backlash to the backlash. Those writers wanted their own offices, and editors wanted privacy, and not everyone wanted to be running into people all the time, because not everyone was actually collaborating, even though their bosses and their bosses’ bosses said that they should, because collaboration, teamwork, and togetherness—these were the new workplace buzzwords. Until they weren’t. Until people realized that they were missing—as architect Ben Jacobson said in a Gensler sponsored panel on the need to create a balance between focus and collaboration—the concept of “parallel play,” i.e. people working next to each other, but not necessarily with each other. Until individuality came back, particularly in San Francisco in the tech scene, and particularly in the iconoclastic start-up tech scene, where people began to want something a little different.

Artist Fills Paris' Negative Space with Whimsical Illustrations

When you're surrounded by buildings on all sides, what do you see? In his SkyArt series, French artist Lamadieu Thomas gives us his answer. He takes claustrophobia-inducing photographs of urban landscapes through a fish-eye lens, framing the sky with rooftops and filling the negative space with playful illustrations. Thomas describes his whimsical approach to art as an attempt to show "what we can construct with a boundless imagination" and "a different perception of urban architecture and the everyday environment around us." To see more from the collection, continue after the break.

The Evolving Symbiosis Between Architects & Developers in the UK

Although the design world has maintained a negative opinion of property developers for a very long time, the relationship between architect and developer has begun to evolve in the United Kingdom. In this article, first published in Blueprint issue #333 as "Why Architects Are Working for Property Developers," the cultural shift is explained and explored through case studies.

Developers have not, traditionally, enjoyed a very good reputation within the architectural fraternity - or with the general public, for that matter. At worst they are seen as sharp-suited pirates of urban space, stripping out centuries-old residential or commercial buildings to replace them with shoddy, design-by-numbers structures, thrown up with no driving objective other than maximising their cash before they move on.

But times have changed. Whether it's economic necessity - driven by the lack of buyers for bad housing or poor office space - or just good sense, there is a growing number of developers out there that appear to be cherry-picking some of the UK's better practices to transform our urban wastelands and unloved spaces. This new breed appears to enjoy and understand the value of architecture and design. Some of them even consider architects their natural collaborators - the creative yang to their commercial yin.

Seaweed, Salt, Potatoes, & More: Seven Unusual Materials with Architectural Applications

The following article is presented by ArchDaily Materials. In this article, originally published by Metropolis Magazine, Lara Kristin Herndon and Derrick Mead explore seven innovative architectural materials and the designers behind them. Some materials are byproducts, some will help buildings breathe and one is making the leap from 3D printing to 4D printing.

When Arthur C. Clarke said that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic, he was speaking from the spectator’s point of view, not the magician’s. As our list of smart materials shows, technology solves difficult problems, but getting there requires more than just a wave of the magic wand. Each of the following projects looks past easy answers. Whether it’s a new way of looking at old problems, a new material that maximizes the efficiency of an old technique, or a new method to tap the potential of an abundant or underutilized resource, here are seven innovators who take technology out of the realm of science fiction.

Pathé's Video Archive Reveals Great Architectural Moments, 1910-1970

The following article originally appeared on Metropolis Magazine as "Five Architectural Highlights from the Pathé Newsreel Archive." It has been slightly adapted to fit ArchDaily's format. The video above, from 1930, shows the Empire State Building under construction.

Newsreel archives are a goldmine for design buffs—and when you have an archive of the size and scope of British Pathé's, there's hours of compulsive watching in store. The famous film and production company recently put up 85,000 of their videos on Youtube, in high definition, for free viewing.

The Parisian Pathé Brothers pretty much invented the newsreel format at the turn of the century, and established their London base in 1902. From 1910 to 1970 they produced thousands of films on events and trends around the world, including, of course, subjects of significance for architecture and design. It's an unparalleled opportunity to see some great classics in their context—with people using them, reacting to them, commenting on them.

Some videos, like a round-up of skyscraper-inspired hats from the 1930s, might not stand the test of time, but others, like a tour of Le Corbusier's Couvent de la Tourette, are priceless. The latter video seems even more precious because it is marked "unused material"—footage that Pathé shot, but never edited into one of their newsreels—meaning that very few people have had a chance to see it before you do now, on your screen.

More outstanding videos to get you started on your newsreel binge, after the break...

Cantilevers on Sand, Ducks in a Bag & Other Adventures: A Conversation with FormlessFinder

Formlessfinder of New York City has a vision "to liberate architecture from the constraints of form." Samuel Medina of Metropolis Magazine recently interviewed the Princeton duo on contemporary architectural practice - fittingly naming them "Formal Renegades."

“We like architecture,” says Garrett Ricciardi, with real sincerity. “We want to save architecture.” But from what? Ricciardi is one half of New York–based formlessfinder, the experimental—you might say radical—architecture firm he founded with Julian Rose in 2011, just after the pair completed a joint thesis at Princeton University. Their project, which laid out the blueprint for Ricciardi and Rose’s subsequent collaborations, advanced a daring proposition: to liberate architecture from the constraints of form.

“The basic idea of the formless is about freeing up architecture to make it about what we want it to be about,” Rose says. “The idea is that form has sort of gotten in the way,” he adds, before checking off a laundry list of offenders: parametricism, digital fabrication, blobs, minimalism. Where form has “always served to limit and control,” the formless, as the architects have come to define it, is subversive by nature. It’s an operation rife with uncertainty, producing “messy, equivocal, and, most importantly, generative” results.

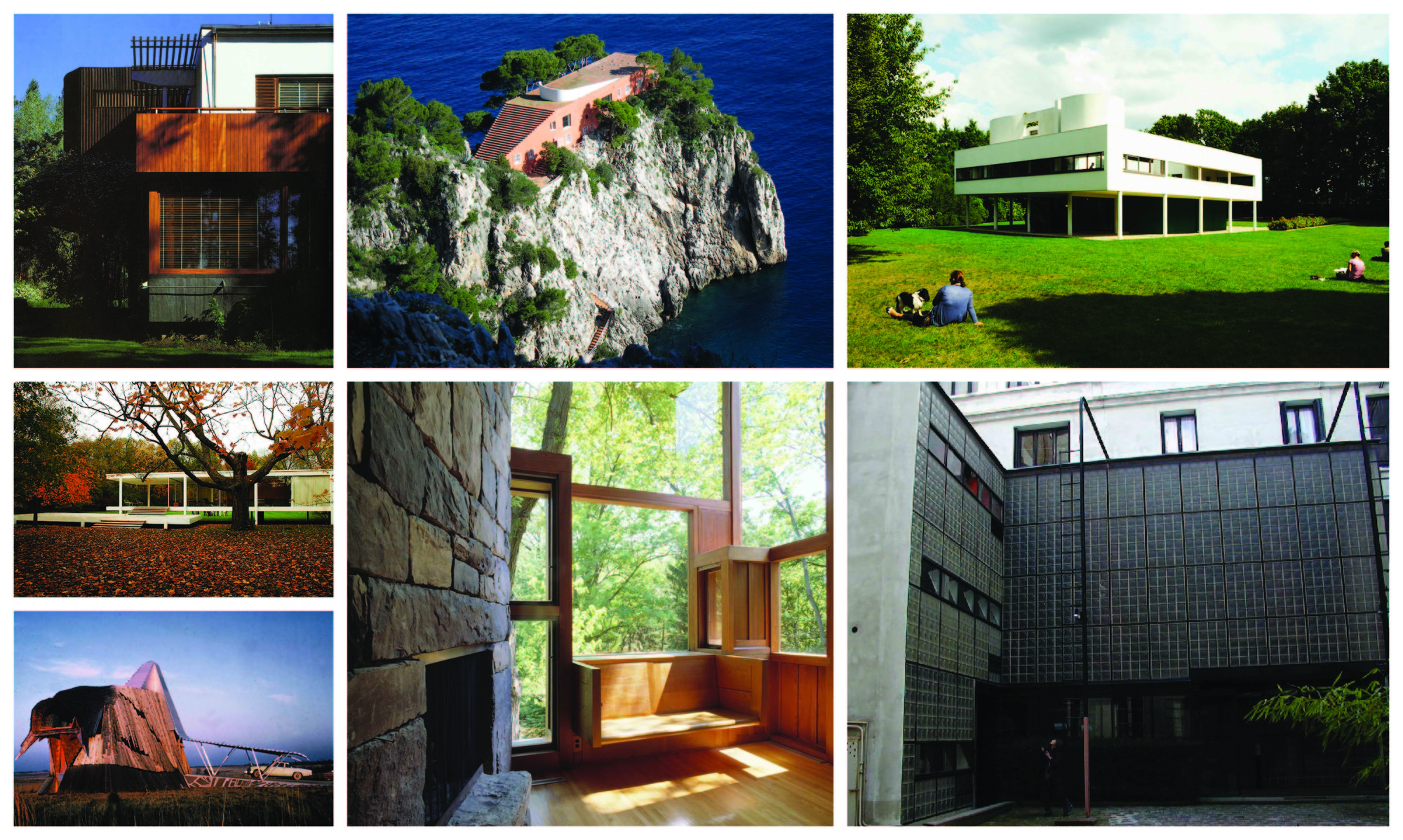

9 Architects Reflect on the Homes That Most Inspired Them

Where do you receive inspiration? Nalina Moses asked the question to nine contemporary residential architects, asking each to choose one residence that had left an impression on them. The following answers were first published on the AIA’s website in the article “Homing Instinct."

When nine accomplished residential architects were asked to pick a house—any house—that has left the greatest impression on them as designers, most of their choices ran succinctly along the canon of American or European Modern architecture. Two—Alvar Aalto’s Villa Mairea and Pierre Chareau’s La Maison de Verre—were even tapped twice.

If the houses these designers chose weren’t surprising, the reasons they chose them were. Rather than groundbreaking style or technologies, what they cited were the moments of comfort, excitement, and refinement they offered: the restful proportions of a bedroom, the feel of a crafted wood handrail, an ocean view unfolding beyond an outdoor stair.

The Fifth Pillar: A Case for Hip-Hop Architecture

The following article by Sekou Cooke was originally published in The Harvard Journal of African American Planning Policy.

Not DJ Kool Herc. Not The Sugarhill Gang. Not Crazy Legs. Not even Cornbread. The true father of hip-hop is Moses. The tyrannical, mercilessly efficient head of several New York City public works organizations, Robert Moses, did more in his fifty-year tenure to shape the physical and cultural conditions required for hip-hop’s birth than any other force of man or nature. His grand vision for the city indifferently bulldozed its way through private estates, middle-class neighborhoods, and slums. His legacy: 658 playgrounds, 28,000 apartment units, 2,600,000 acres of public parks, Flushing Meadows, Jones Beach, Lincoln Center, all interconnected by 416 miles of parkways and 13 bridges. Ville Radieuse made manifest, not by Le Corbusier, the visionary architect, but by “the best bill drafter in Albany.”

This new urbanism deepened the rifts within class and culture already present in post-war New York, elevated the rich to midtown penthouses and weekend escapes to the Hamptons or the Hudson Valley, and relegated the poor to crowded subways and public housing towers—a perfect incubator for a fledgling counterculture. One need not know all the lyrics to Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message” or Melle Mel’s “White Lines” to appreciate the incendiary structures built by Moses and his policies. As the Bronx began to burn, hip-hop began to rise.

What If MOMA Had Expanded Underground (And Saved The American Folk Art Museum)?

In January of this year, the latest work by Smiljan Radic, the Chilean architect chosen to design the next Serpentine Pavilion, opened to public acclaim. The Museum of Pre-Columbian Art (Museo de Arte Precolombino), located in Santiago de Chile, is a restoration project that managed to sensitively maintain an original colonial structure - all while increasing the space by about 70%.

Two days before the The Museum of Pre-Columbian Art opened, the Museum of Metropolitan Art (MOMA) in New York issued a statement that it would demolish the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM), designed by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects, in order to accomplish its envisioned expansion. Two weeks ago, preparations for demolition began.

Some background: MOMA had hired Diller Scofidio + Renfro a year earlier to design the expansion. The office asked for a period of six months to consider the possibilities of integrating the American Folk Art Museum into the design. After studying a vast array of options (unknown to the public) they were unable to accommodate MOMA’s shifting program needs with the AFAM building. They proposed a new circulation loop with additional gallery space and new program located where the AFAM is (was) located.

What appears here is not strictly a battle between an institution that wants to reflect the spirit of the time vs a building that is inherently specific to its place. It represents a lost design opportunity. What if the American Folk Art Museum had been considered an untouchable civic space in the city of New York, much like the The Museum of Pre-Columbian Art is for the city for Santiago? Then a whole new strategy for adaptive reuse would have emerged.

The Story of Maggie's Centres: How 17 Architects Came to Tackle Cancer Care

Maggie's Centres are the legacy of Margaret Keswick Jencks, a terminally ill woman who had the notion that cancer treatment environments and their results could be drastically improved through good design. Her vision was realized and continues to be realized today by numerous architects, including Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, and Snøhetta - just to name a few. Originally appearing in Metropolis Magazine as “Living with Cancer,” this article by Samuel Medina features images of Maggie's Centres around the world, taking a closer look at the organization's roots and its continued success through the aid of architects.

It was May 1993, and writer and designer Margaret Keswick Jencks sat in a windowless corridor of a small Scottish hospital, dreading what would come next. The prognosis was bad—her cancer had returned—but the waiting, and the waiting room, were draining. Over the next two years until her death, she returned several times for chemo drips. In such neglected, thoughtless spaces, she wrote, patients like herself were left to “wilt” under the desiccating glare of fluorescent lights.

Wouldn’t it be better to have a private, light-filled space in which to await the results of the next bout of tests, or from which to contemplate, in silence, the findings? If architecture could demoralize patients—could “contribute to extreme and mental enervation,” as Keswick Jencks observed—could it not also prove restorative?

"Lebbeus Woods - Architect" Returns to NYC

This summer, the drawings, theories and works of architect Lebbeus Woods are headed to the city that Lebbeus considered home. After a five-month stay at SFMOMA, the exhibit "Lebbeus Woods - Architect" will be at the Drawing Center in SoHo, Manhattan until mid-June. The following story and overview of the exhibition, by Samuel Medina, originally appeared at Metropolis Magazine as “Coming Home".

It’s all too biblical an irony that Lebbeus Woods—architect of war, catastrophe, and apocalyptic doom—died as strong winds, rain, and waves barreled down on Manhattan, his home for some 40-odd years. Woods passed the morning after Hurricane Sandy flooded Lower Manhattan, almost as if the prophet had succumbed to one of his turbulent visions. But this apocryphal reading is just one way to view Woods’s work, which, as often as it was concerned with annihilation, always dared to build in the bleakest of circumstances.

Grimshaw Architects Merge Architecture and Industrial Design at Milan Furniture Fair

Grimshaw Architects' dual focus on industrial and architectural design will be celebrated this month in a featured exhibit at Milan Furniture Fair. In this article, originally published by Metropolis under the title "Down to the Details," author Ken Shulman presents the firm's evolution in the context of the exhibit, touching on the projects being presented and more intriguingly — on how they are being presented.

Shortly after he joined Grimshaw Architects, Andrew Whalley was tasked with putting together an exhibition at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in London. Titled Product + Process, the 1988 show was decidedly counter-current—a parade of pragmatic, largely industrial structures Grimshaw realized in the UK in the face of surging postmodern fervor. Featured projects included the transparent building the then 15-person firm designed to house the Financial Times’ London printing facilities, and a flexible, easily reconfigurable factory Grimshaw built for Herman Miller in Bath. But it wasn’t the selection of projects that caught the public eye. “We asked our clients to take apart pieces of their buildings, and then rebuild them for the exhibition,” says Whalley, now deputy chairman of Grimshaw. “This wasn’t a typical show of architectural drawings and models.”

The Steel Age Is Over. Has The Next Age Begun?

Andrew Carnegie once said, “Aim for the highest.” He followed his own advice. The powerful 19th century steel magnate had the foresight to build a bridge spanning the Mississippi river, a total of 6442 feet. In 1874, the primary structural material was iron — steel was the new kid on the block. People were wary of steel, scared of it even. It was an unproven alloy.

Nevertheless, after the completion of Eads Bridge in St. Louis, Andrew Carnegie generated a publicity stunt to prove steel was in fact a viable building material. A popular superstition of the day stated that an elephant would not cross an unstable bridge. On opening day, a confident Carnegie, the people of St. Louis and a four-ton elephant proceeded to cross the bridge. The elephant was met on the other side with pompous fanfare. What ensued was the greatest vertical building boom in American history, with Chicago and New York pioneering the cause. That’s right people; you can thank an adrenaline-junkie elephant for changing American opinion on the safety of steel construction.

So if steel replaced iron - as iron replaced bronze and bronze, copper - what will replace steel? Carbon Fiber.

.jpg?1397700541)