For several years now, the countryside has ceased to function merely as a picturesque counterpoint to the city and has instead become an active laboratory for new relationships between territory, landscape, and people. Here, environmental urgency meets collective memory; ancestral techniques converse with architectural experimentation; and local communities act as curators of their own territory. Contemporary rurality emerges less as a geography and more as a culture—inscribed in ways of life that care for the environment.

It is a vast rural expanse spread across the planet, assuming different expressions depending on context—from Asian rice fields to African agricultural settlements, from small European farms to the large estates and agro-extractive communities of the Americas. Yet, beneath this plurality, is there something that unites them? And, more importantly, how might architecture illuminate this quiet thread?

To situate this debate, it is worth revisiting Bernard Kayser’s classic definition, according to which rural regions are characterized by low population density, predominance of vegetation, and activities linked to agro-silvo-pastoral systems. Kayser, however, offers a warning: the rural should neither be interpreted through an urban lens nor reduced to nostalgia. It embodies a distinct way of relating to territory, one rooted in the local. This rootedness makes the notion of a homogeneous “rural society” impossible; instead, it gives rise to complex ecosystems of coexistence, shaped by global networks of production, communication, and imagination.

It is within this scenario that rural architecture emerges as fertile ground for experimentation. As diverse as the planet itself yet threaded with silent convergences, it enters 2025 with shared reflections. This becomes evident in the projects published throughout the year on ArchDaily—in works that employ local materials such as bamboo, rammed earth, and timber; techniques passed down through generations; and architectures that regard climate as a partner and community as co-author.

This is a rural architecture that neither fetishizes tradition nor idealizes progress as rupture. It turns the everyday—the convergence of memory, labor, and landscape—into built matter. If the countryside has conventionally been tied to the past and the city to the future, these projects invert that perspective: they present the rural as a horizon capable of anticipating another vision of the future—one that coexists with nature, honors the local, and materializes what the territory itself offers.

Below, we present some rural projects from 2025 that, even in different contexts, make visible this way of inhabiting and constructing the countryside.

Pavilions and Installations: The Gesture as Architecture

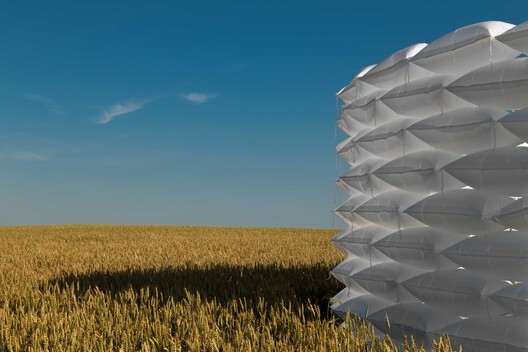

In the contemporary moment, the countryside becomes a stage for inquiry—a place where architecture tests limits and invites sensory experience. In this setting, installations and pavilions proliferate, inviting direct contact with nature, sometimes surfacing questions of care and sustainability, other times reactivating community gestures and ancestral ways of life.

In these structures, architecture arises from the human gesture: the interwoven bamboo that becomes a collective shelter in the Bamboo Theater; the tower that turns the horizon into a pathway in Hito Entrelazos; or the ground that records human passage in Trace of Land. Minimal in scale yet existential in impact, they activate values tied to memory, encounter, and contemplation. Whether in Taiwan, Chile, or any other latitude, they draw on a shared language—the gesture that becomes lived space, capable of conveying collective perceptions without resorting to monumentality.

Bamboo Theater / Cheng Tsung FENG Design Studio

Hito Entrelazos Watchtower / Javiera Muñoz Olave

Phoenix Feather Tea Pavilion / Kong Xiangwei Studio

Trace of Land / ELSE

SoftPower Installation / Gregory Orekhov

Rural Institutions: Learning With the Landscape

In rural regions, school architecture is more than a shelter for educational activities; it brings communities closer to an essential service that strengthens social ties and expands possibilities for the future. Where physical distance, inadequate infrastructure, and territorial dispersion often limit access to education, the building becomes a concrete tool of equality—a meeting point capable of weaving together knowledge, care, and belonging.

In this context, projects like the Hiwali School in India and the Hway Ka Loke School in Thailand begin with the land itself. The former rises from the terrain, transforming topography into learning space; the latter dissolves boundaries between inside and outside, inviting the community into the campus. In both cases, architecture functions as a pedagogical tool: clay brick becomes embodied knowledge, and courtyards and open areas shift from formal devices to forms of coexistence adapted to climate and local ways of life.

Hiwali School / pk_iNCEPTiON

Rainbow International School / Spacefiction studio

Hway Ka Loke School / Simple Architecture

Museums and Cultural Spaces: Preserving, Activating, Designing

In rural territories, culture reveals itself in what remains inscribed in memory. When a space like La Panificadora in Ecuador creates a communal environment for producing and learning about bread, architecture does more than establish “programs”: it reactivates gestures already rooted in the landscape—work, craft, encounter. The land becomes a living archive, and architecture merely gives it form.

In another direction, the ET-302 Memorial in Ethiopia operates in an intimate register, materializing collective mourning in the very place where trauma occurred. In this sense, cultural architecture in rural areas rarely emerges from an invention ex nihilo, but rather from a sensitive interpretation—sometimes activating community practices, other times holding memory. Its value lies less in grandeur than in its ability to reveal the latent meaning of the territory.

La Panificadora Centro desarrollo y de producción rural / Natura Futura

Khanong Phra Campsite / PHTAA Living Design

The ET-302 Memorial / Alebel Desta Consulting Architects and Engineers

Living in the Countryside: Refuges of the Present

To inhabit the rural today is neither to revive idyllic images of the past nor to project technological utopias onto the future. What these houses show is an ethics of the everyday: living in the countryside means learning to coexist with the rhythms of labor, the intimacy of domestic life, and the constant presence of the environment.

Projects such as the Teacher’s House in the Dominican Republic, which adapts to the rhythms of a small community, and Housing NOW in Myanmar, which offers rapid housing using lightweight systems of local bamboo, show that rural architecture emerges from daily life. It responds to concrete needs, accommodates ways of living, and shapes itself to context rather than imposing a style. By incorporating available materials and touching the land lightly, these projects create continuity between what already exists in the territory and what is now taking shape.

Teacher's House / Øblicuo

Butterfly House / Tallerdarquitectura

Housing NOW / Blue Temple

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topic: Year in Review, proudly presented by GIRA.

GIRA sets the standard where architectural design meets intelligence. From the defining moments of 2025 to the innovations shaping 2026, we create smart solutions that elevate living and working environments with timeless aesthetics. Join us in shaping the future of architecture and interior design — where vision becomes reality.

Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.