The Benedictine Monastery of San Nicolò l’Arena in Catania, Sicily, holds within its stones the echoes of five centuries, shaped by time, varied uses, violent earthquakes, and the blazing force of Mount Etna. Its walls, silent witnesses to history, were molded both by the fire of nature and by human hands. Yet among all the transformations it underwent, none was as profound or poetic as the one led by Italian architect Giancarlo De Carlo, starting in 1980. After 30 years of dedicated work, time required to truly understand such a complex and awe-inspiring site, the former monastic residence was reborn as a university, not by force, but through revelation.

“It is rare for an architect to engage with such a complex blend of architectural emotions.” This statement captures the challenge De Carlo faced when tasked with transforming the Monastery of Catania. The complexity starts with its history. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the monastery was founded in 1558 and is considered a masterpiece of late Sicilian Baroque architecture. Its original plan featured a square layout with a central courtyard—the "Marble Cloister"—named for its lavish use of marble.

But this rich architecture faced a series of setbacks. The first came in 1669, when nearby Mount Etna erupted. Amid smoke and ash, lava reached the city walls and surrounded the monastery’s north and west sides. Though the structure survived, its surroundings were drastically altered, buried under walls of lava that reshaped the landscape into a stony, lunar-like terrain. Then, in 1693, disaster struck again: a devastating earthquake hit Catania, registering 7.7 on the Richter scale. While the basement and part of the 16th-century ground floor remained, only 14 columns of the cloister stood; the rest were destroyed.

In 1702, nine years after the quake, reconstruction began. Monks from other monasteries moved in. The new building expanded upon the original. The Marble Cloister was rebuilt with late-Baroque flourishes. A second cloister was added to the east, featuring a garden and eclectic-style cafés. On the northern side, a new section was created for communal monastic activities. Two gardens were also planted atop the hardened lava. With these additions and embellishments, the Monastery of Catania became one of the largest in Europe.

In 1866, under expropriation laws, the monastery was seized by the state. Over time, it was repurposed to host schools, public gyms, and military barracks. Each new use left its mark. Frescoes were removed, corridors subdivided, and new rooms were added for offices, classrooms, and bathrooms. A hospital was built over what was once a botanical garden. These civilian uses lasted until the late 1970s, when the building was left nearly abandoned.

The most significant turning point came in 1977, when the municipality donated the monastery to the University of Catania as part of a project to regenerate the city’s historic center. It was to house the Faculty of Humanities. In this context, the university invited Giancarlo De Carlo in 1980 to advise on how the building could be restored and adapted for its new academic function. After his first visit, De Carlo recommended holding a national design competition, but none of the submissions met the needs of either the building or the institution. In 1983, the university asked De Carlo to create a “Progetto Guida” (Design Guidelines) and take part in the transformation himself. This began a restoration process that lasted three decades—during which the site’s history was rediscovered, from the Roman era to the present. Beneath the monastery, entire Roman neighborhoods and houses from the Hellenistic and Imperial periods were found and thoughtfully integrated into the new design.

The transformation was guided by the insertion of contemporary elements that would give the space a renewed identity. The original structure was restored and brought back into view, while the new additions carefully echoed its architectural language. Through a delicate dialogue between past and present, the line between old and new nearly disappears, resulting in a seamless whole composed of many layers of time. De Carlo described this approach as one that favors removing over adding, restoring over replacing, and creating networks of connection rather than simply redefining parts.

There is no separation between preservation and design. One must move between tradition and innovation so that new ideas, comparisons, interpretations, and proposals can keep evolving—avoiding both the imitation that comes from revering the past and the superficiality that can come from blind innovation. The value of a project lies in its ability to transform, to enter the different architectural layers of a place, and to become a new layer that reshapes the meaning of the others. – Giancarlo De Carlo

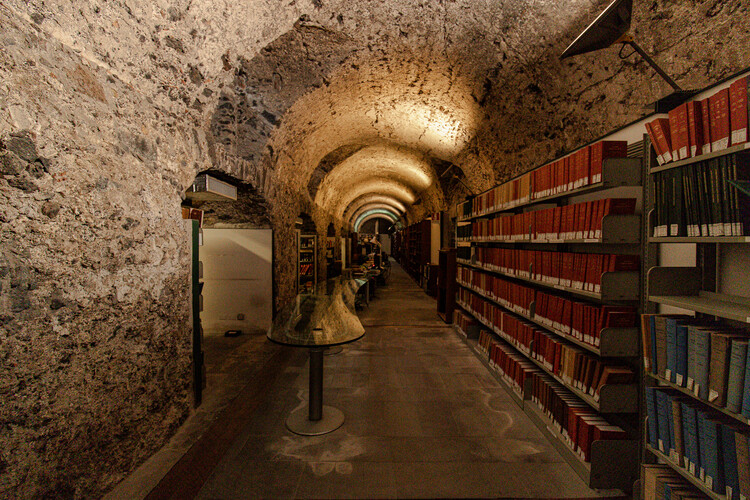

Walking through the restored building, one is constantly confronted by its history. In the main courtyard, ruins remain visible. What once were the monastery stables are now classrooms. Inside the university library, a Roman domus—complete with its central patio—can still be seen, fully integrated with the 16th-century monastery and the new suspended structures that provide students with access to the space. The redesigned gardens, featuring a fountain and terrace, the spiral staircase, and the thermal center built atop solidified lava, all add to the narrative. This center, enclosed in glass and topped by a sculptural chimney, merges past and present. Among all the interventions, the red ceiling of the “Sala Rossa” stands out. It not only functions as a ceiling but also as the structural floor of the refectory above—damaged by Etna. Its shape evokes a volcano, and like many other gestures in the project, brings the monastery closer to the city and its people. It reflects what De Carlo firmly believed:

With its real, three-dimensional structure, [the project] becomes a space where young people move from one point to another—a place full of air, light, communication, expectation, and promise. Through new readings and experimental design, old meanings have been replaced by a new one—allowing ancient architecture to take on a new structure and a renewed role in the contemporary world. – Giancarlo De Carlo

In this intricate blend of architectural emotion, De Carlo’s work did more than restore a building—it gave the place back its essence: the ability to shelter human life in its constant transformation. Between lava, light, and rebirth, this architecture—so insistent on surviving—finds new ways to reinvent itself. And perhaps, this is where its greatest beauty lies: in being unfinished, open, and alive—just like time itself.

This feature is part of an ArchDaily series titled AD Narratives, where we share the story behind a selected project, diving into its particularities. Every month, we explore new constructions from around the world, highlighting their story and how they came to be. We also talk to the architects, builders, and community, seeking to underline their personal experiences. As always, at ArchDaily, we highly appreciate the input of our readers. If you think we should feature a certain project, please submit your suggestions.