Every natural disaster has an "aftershock" in which we realize the fragility of our planet and the vulnerability of what we have built and created. We realize the threat to our lifestyles and the flaws in our design choices. The response to Hurricane Sandy in October 2012 was no different than the response to every other hurricane, earthquake, tornado , tsunami or monsoon that has wrought devastation in different parts of the world. We recognize our impact on the climate and promise to address how our development has caused severe disruptions in the planet's self-regulating processes. We acknowledge how outdated our systems of design have become in light of these damaging weather patterns and promise to change the way we design cities, coastlines and parks. We gradually learn from our mistakes and attempt to redress them with smarter choices for more sustainable and resilient design. Most importantly, we realize that we must learn from how natural processes self-regulate and apply these conditions to the way in which we design and build our urban spaces.

Since Hurricane Sandy, early considerations of environmentalists, planners and designers have entered the colloquiol vocabulary of politicians in addressing the issues of the United States' North Atlantic Coast. There are many issues that need to be tackled in regards to environmental development and urban design. One of the most prominent forces of Hurricane Sandy was the storm surge that pushed an enormous amount of ocean salt water far inland, flooding whole neighborhoods in New Jersey, submerging most of Manhattan's southern half, destroying coastal homes along Long Island, and the Rockaways and sweeping away parts of Staten Island. Yet, despite the tremendous damage, there was a lot that we learned from the areas that resisted the hurricane's forces and within those areas are the applications that we must address for the rehabilitation and future development of these vulnerable conditions. Ironically, one of the answers lies within Fresh Kills - Staten Island's out-of-commission landfill - the largest landfill in the United States until it was shutdown in 2001. Find out how after the break.

Fresh Kills Landfill was opened in 1947 along the western coast of Staten Island as a temporary solution for New York City's waste just in time to accommodate an exponential rise in consumption in the post-World War II United States. Three years later, and the landfill continued to operate until it became the principal landfill for New York City, collecting the solid waste from all five boroughs in the "age of disposability". It is no wonder then, that the temporary solution swiftly became a 50-year one.

The cultural dynamics of the United States had changed in the years that followed World War II. Every veteran came back with the opportunity to buy a private home in the suburbs and start a family, while a technological explosion brought the military's reappropriated technology into every household via microwaves, refrigerators, dishwashers, washing machines - and, of course, non-biodegradable plastics for every application. As the population exploded, so did its consumption of unrecyclable and disposable goods. Thus the landfill - once a 2,200-acre, sea level wetland - turned into 2,200 acres of hills as high as 200-feet that buried nearly 30,000 tons of trash daily by the 1990s. During its operation until 2001, the dump was the largest landfill in the world. It remains to be the largest-man made structure: what we see today as undulating 200-foot hills is actually buried garbage.

But the story of Fresh Kills does not end there. In fact, it is likely that within the next few decades, the perception of the former dump will have changed significantly with a few reprisals along the way...

By the time of its closing in 2001, the city and state governments had recognized the negative impacts of the landfill on nearby communities. Congresswoman Susan Molinari spoke at a press conference that announced the closing, citing it as "one of the worst nightmares from a social, environmental and health impact that has affected Staten Islanders". And politicians claimed to have understood how not to treat solid waste, communities and the environment

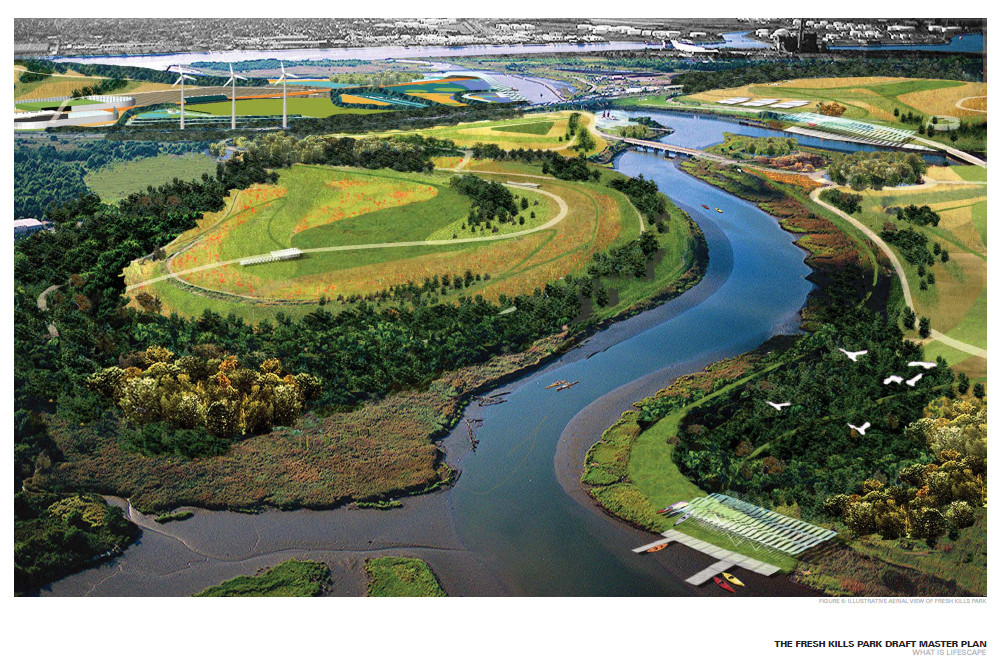

Over the last decade that Fresh Kills has closed, the Department of City Planning along with New York Department of State’s Division of Coastal Resources has developed a 30-year master plan to regenerate the decommissioned landfill into New York City's largest park which will include five main areas that encompasses natural habitats for wildlife, the resurgence of the natural topography, programming for a variety of activities and circulation throughout the 2,200-acre expanse. The five areas will be composed of The Confluence - cultural and recreational waterfront park that includes Creek Landing with access to the city's waterways and areas for gathering and recreation and The Point with sports fields and event spaces; North Park - vast natural settings featuring footpaths and trails of scenic overlooks; South Park - active recreational areas; East Park - connections to existing roadways and routes with programming for nature education areas; and West Park - an earthwork monument on a vast hilltop.

Renowned Landscape Architecture firm, James Corner Field Operations won the 2001 competition to design the park and its vast areas over the next thirty years, actively incorporating sustainable energy infrastructure. Natural gas collection from the decomposing waste will be used to heat approximately 22,000 homes, and photo-voltaic cells, wind turbines, and geothermic heating and cooling will be considered for the parks' development to keep to the city's sustainable energy commitments. The Land Art Generator Initiative hosted a competition last year for designs of sustainable infrastructure within Fresh Kills. The diverse results can be viewed here where designers are exploring ways to address these topics throughout the park.

The planning, which can be found on NYC.gov's website is broken down into three ten-year phases, the first of which includes opening South and North Park and the Confluence to the public, completing a roadway to connect to the West Shore Expressway, opening of recreational facilities, early programs for non-profit and commercial development, and closing and capping the East and West mounds of the landfill, according to the Draft Master Plan. Currently, Fresh Kills Park hosts an annual Sneak Peak at the park's development (this year's is scheduled for September 29th, 2013) which allows the public to preview its transformation.

Despite the vast devastation wreaked by Hurricane Sandy, the storm helped prove exactly how important the initiative to redevelop Fresh Kills Park really is, and contributed to establishing the long held belief that our coastlines are incredibly important to the protection of inland areas. Michael Kimmelman revisits the significance of the Fresh Kills landscape in an article in the New York Times late last year. The wetlands and natural vegetation of the park, which has grown in since the landfill being filled in 2001, helped buffer the impact on neighboring residential areas in Travis, Bulls Head, New Springville and Arden Heights. The permeable soil of wetlands absorb much of the storm surge and redistribute the accumulating water in ways that concrete and asphalt cannot.

The value of Fresh Kill Landfill / Park is indelible to the protection of neighborhoods. Once a curse on the communities, the 2,200-acres of land has proven to be a savior for those same communities. Coastal buffers through vegetation and natural development are not new to city planning discourse. States throughout the East Coast of the United States have developed numerous initiatives to keep these areas unsettled and develop waterfront parks that could absorb the brunt of the tumultuous Atlantic Ocean. There are many options to creating buffers and protection against storm surge, some of which we discussed in an earlier article on ArchDaily.

But some of the most effective methods of dealing with natural disasters is mitigating their impact rather than attempting to stop them altogether. We cannot rely solely on man-made systems when they do not adapt to changing impacts. We can build floodgates, dams and dikes such as exist in the Netherlands, but this may cause further damage to self-regulating ecosystems and will require constant redevelopment as storms continue to ravage the coast. The redevelopment of our coastlines calls for the consideration of natural solutions that are developed with coastal erosion in mind. Governor Cuomo of New York passed into a law a buyout program that would encourage longtime residents in flood prone regions along the coast to sell their damaged homes and property to the government to be redevelopment into coastal reefs, wetlands and parkland that could serve as buffers for future storms. The program is voluntary but the initiative recognizes the significance and dangers of urban development along flooding regions. Even considerations to develop wetlands along Manhattan's exposed south-east coast have been introduced by design firms Architecture Research Office and DLAND Studio.

The impact of Hurricane Sandy has been significant and has reverberated throughout the design community as we struggle to determine future solutions before another storm hits with as much severity. We have acquired a sense of vulnerability that proves just how unsustainable and non-resilient our urban development and infrastructural growth has been to natural disasters. Preparation and resilience should be as key to our vocabulary as sustainability has been in the past decade. This involves altering our cultural wiring when it pertains to our relationship with the environment.

While Fresh Kills Landfill helped preserve 2,200 acres of land for eventual park use, it is a significant lesson in the rampant growth of our consumption. It is true that the landfill has been decommissioned and the land will now go through years of reclamation, but our rate of consumption has not slowed. NYC's trash has simply been rediverted to several dumps in New Jersey. This is not a solution, it is a distraction from the bigger issue of the way we consume and dispose of products and produce non-recyclable goods with a short life of functionality. We produce goods that we consider disposable because it is easier to replace than to fix.

San Francisco has been on track to solving the root of this problem with a commitment to Zero Waste by 2020. An ambitious program of waste management and a series of ordinances that began in the 1990s have been established to alter the culture of disposal and consumption. Residents are first encouraged and then ordered to sort their trash into recycling and composting bins to avoid their accumulation in landfills. So far, SF claims to divert 80% of its solid waste from landfills and hopes that by 2020 this number will reach 100. In this way, citizens are forced to consider the impact of the non-recyclable and non-reusable products that they purchase and dispose of, and enforce a conscious effort to make responsible choices about what can be reabsorbed into the market. This is a change in the culture of disposability onset by the overabundance of goods in the mid 20th century - the "throw-away era" as reported by Kirk Johnson.

When we consider the impact that landfills have on nearby communities, on ecosystems, on our environment; when we have to ask why we don't want to live near a landfill, when we consider what the world can look like without landfills that occupy 3.5 square miles and are instead filled with parkland, recreational areas and healthy ecosystems, it should be enough encouragement to change the way in which we participate in the market and change our relationship to consumption.