Let’s begin with the obvious: kids like to climb, and run, and get their hands on anything that could (and probably will) break. They like to explore and imagine, create and destroy and create again.

Thankfully, a movement in the world of Education has begun to account for this reality (see:Ken Robinson’s seminal 2007 TedTalk), to leave behind the antiquated schema that children are little adults, and to engage students’ creativity, energy, and need for expression – a task often complicated by the physical constraints of a traditional classroom.

When designing a classroom, architects are keenly aware of the importance of the physical conditions of a learning environment (temperature, crowding, even permeability to the community) on a child’s psyche. [1] However, as much as we depend upon studies to help us design the “correct” environment, what we ultimately need is a practical, playful perspective that understands what excites and engages children.

We need a source of inspiration. To look at spaces that welcome interaction with the environment and encourage the free reign of energy and imagination. We need the playground.

A child is visually stimulated by a playground off the bat; from color to scale, the playground has been designed with his interest in mind. Not so shockingly, schools often incorporate color and familiar images to similarly appeal to their students’ sensibilities (most notedly in the Aadharshila Vatika School in India). However, I would suggest that the visual layout of a playground, not just the color palette, has more to offer us as a point of inspiration. Take the sculptural playground of ANNABAU. Like most playgrounds, it has a variety of activities for kids to play on; however, ANNABU’s uses a loop-like structure that dips and rises as kids climb along it, allowing the space to be seen and understood as a continuous sequence of ordered activities.

Similarly, many contemporary classroom designs create activity areas, differentiated by interest or learning mode (visual, experimental, individual, group, etc). We can see this type of flexible lay-out in the Discovery Charter School in Newark, New Jersey, a one-room school. Much like a playground, the room is described as a ‘vast scenario’ of students and teachers, separated into different workstations by colors, movable tables, and low partitions. [2]

However, in large schools where the noisy one-room model wouldn’t suffice, a different type of structure needs to be considered. The loop is the perfect contender to connect these spaces with well-organized, open pathways that give children the freedom to move from one to the other, consciously aware of the expected sequence, while being supervised by their teachers [3].

This was the idea behind the oval-shaped Fuji Kindergarten in Tokyo, Japan, which was designed to “allow children to mix and move around at will.” The pedagogy of learning modules perfectly lends itself to the structure of the loop, or oval as in the case of the Fuji school; in this way the school day is spatially understood as a circuit of activities that gives children flexibility of movement and the sensation of play. [4]

Taking Risks and Making Nooks

The ANNABAU playground aside, most playgrounds contain high-reaching structures that provide a thrilling challenge to young climbers. As Mary Gutmann, architectural history professor at City College, notes in a New York Times article: “The intention is to fall. You don’t want to make the environment so safe that it’s not challenging.” [5]

The playground offers an environment where falling is encouraged, but getting back up expected. It is an environment of risk and recovery, the active climb followed by the moment of rest.

I would imagine that any school would find a climbing structure in the classroom to be problematic (to say the least). However, few would disagree that the classroom of the future should encourage a risk-taking attitude (prerequisite for creative thinking). Moreover, it should also account for the child’s need not just to climb, but to experience the moment of reflective rest that follows.

You may have noticed that most playgrounds also offer tunnels and hidden spaces: the kinds of places where children retreat from the world and let their imaginations run wild. In their article “Landscape for Learning,” Louis Torelli, M.S.Ed. and Charles Durrett, Architect, maintain that children need to occasionally separate from the group and have the sensation of solitude, and suggest that “private and semi-private environments are critical to the development of the young child’s self-concept and personal identity.” [6]

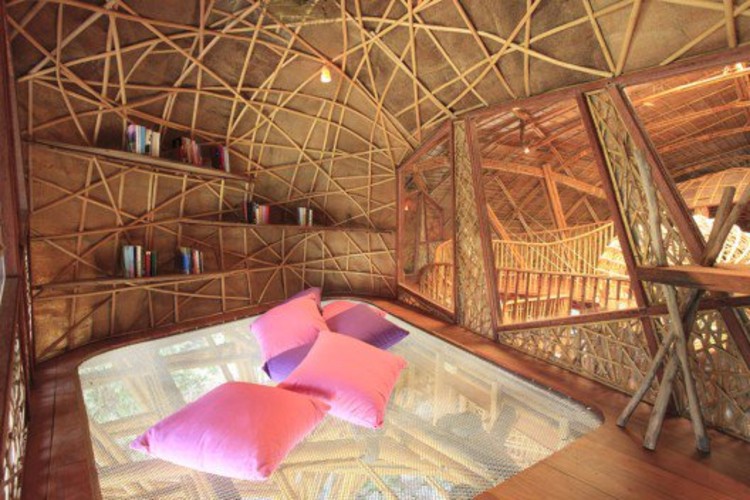

While a tunnel may be impractical for the classroom, if we juxtapose these two elements of a child’s psychology – the desire to climb and the need for retreat – another type of structural solution emerges: the lofted nook.

While breakaway spaces are fairly common in classroom designs, the Seven Fountains School in South Africa has designed ‘creativity’ spaces that are lofted – to much acclaim (the school was awarded an Award of Excellence by the South African Institute of Architects and selected as one of the Exemplary Educational Facilities of 2011 by the OECD, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

70ºN Arkitektur‘s Kindergarten design (featured in the picture above) provides adjustable, climbable playing walls that create intimate reading nooks and lofted mezzanines. Here we see two solutions to the challenges of the modern, multifunctional classroom, solutions that – critically – take into account a child’s perspective.

By examining the physical space of the playground, we open ourselves up to designing a school grounded in the principles of play: a space unrestricted by the expectations of adults, where children interact with the world on their own terms. If the goal of a 21st century education is to activate creativity, then the school designs of the future should look to the playground to create, not landscapes for learning, but playscapes .

References

“The Effect of the Physical Learning Environment on Teaching and Learning.” The Victorian Institute of Teaching.

[2] “Reimagining the Classroom: Opportunities to Link Recent Advances in Pedagogy to Physical Settings.” The McGraw Hill Research Foundation. http://mcgraw-hillresearchfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Reimagining_the_Classroom_DeGregoriFINAL.pdf>

[3] “Classroom Design and How It Influences Behavior.” Early Childhood News.

[4] “Best Practices in Educational Facilities Investments: Fuji Kindergarten, Tachikawa, Tokyo, Japan.” Centre for Effective Learning Environments (CELE).

[5] Shattuck, Kathryn. “For Youngsters, Leaps and Boundaries.” The New York Times.

[6] Durrett, Charles and Louis Torelli. “LANDSCAPE FOR LEARNING: THE IMPACT OF CLASSROOM DESIGN ON INFANTS AND TODDLERS.” Spaces for Children.

Photos