I spent much of the nineties living in Tokyo, but it wasn’t until I had left that Ryuichi Sakamoto’s(1) music began to inform me about its complex environments.

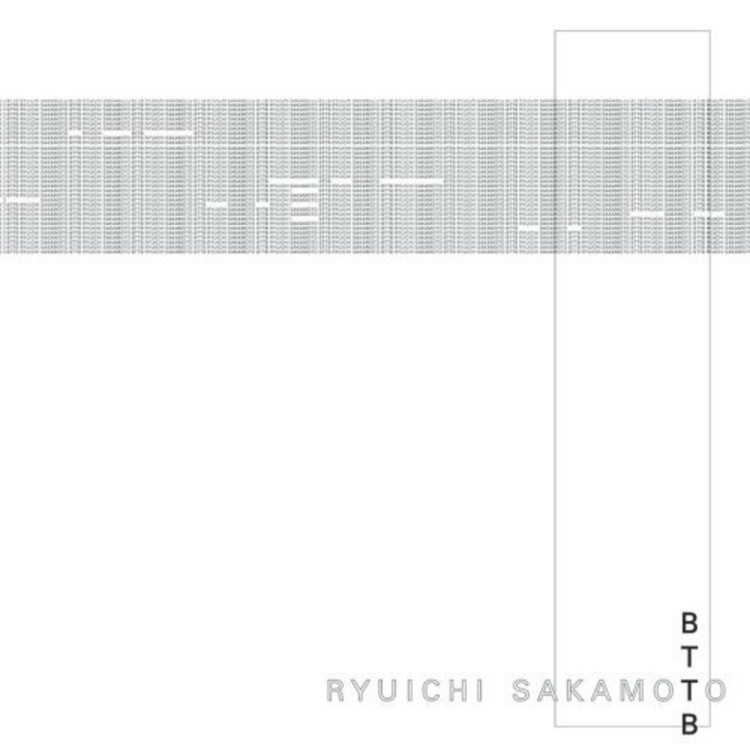

His album, somewhat ironically (I think) titled BTTB, or, Back to the Basics, came out way back in 1999. Though post-dating my Tokyo Period, it sonically completed my memories of that city. Having leapt through time, it resolved my incomplete Tokyo soundtrack.

BTTB tries to be minimal, but, like the city it came from, struggles with complexity(2). Its opulent density made it seem like the piano had been miked on the inside, my ear forced down to the machinery of strings. The tension between richness and absence I perceived reminded me of trying to find my way in and around all of Tokyo’s jumbled systems.