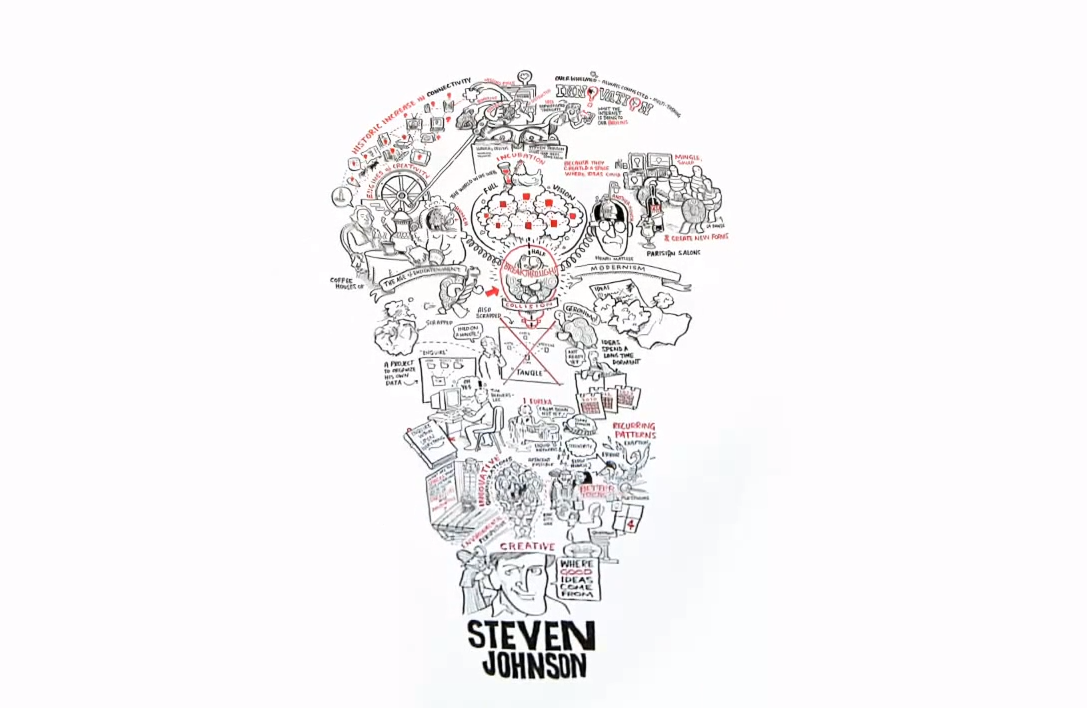

What do MIT’s Building 20, the Ancient Greek Agora, 18th Century British teahouses, and early 20th century Parisian cafés have in common?

They were some of the most creative spaces in the world.

People who gathered there would interact. People, such as Socrates or Chomsky or Edison, exchanged ideas, argued about morals, and discussed technologies. They participated in an informal discourse driven by passionate involvement.