The colorful houses of Aswan in the south of modern-day Egypt attract tourists who venture that far up the River Nile. Accessed by small river boats, islands like Suheil West are the homes of Nubian communities, some of whom had had to relocate after the building of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s. Behind the picturesque views of plastered walls covered in murals and motifs, perched on rocky hills overlooking the Nile, is a construction technique used locally for centuries. It uses locally sourced materials, conserves nature, and regulates internal temperatures against the heat in the day and the cold at night.

Nubia refers to a region on the Nile valley in the middle of the eastern Sahara Desert, bridging the border between Egypt and Sudan. Its extents varied in history, but modern-day Nubian speakers on the Nile live approximately between the towns of Aswan in Egypt and Dongola in Sudan. The landscape is characterized as rich and fertile along the river, surrounded by rocky, arid desert. Naturally, this affected customs such as food and building techniques.

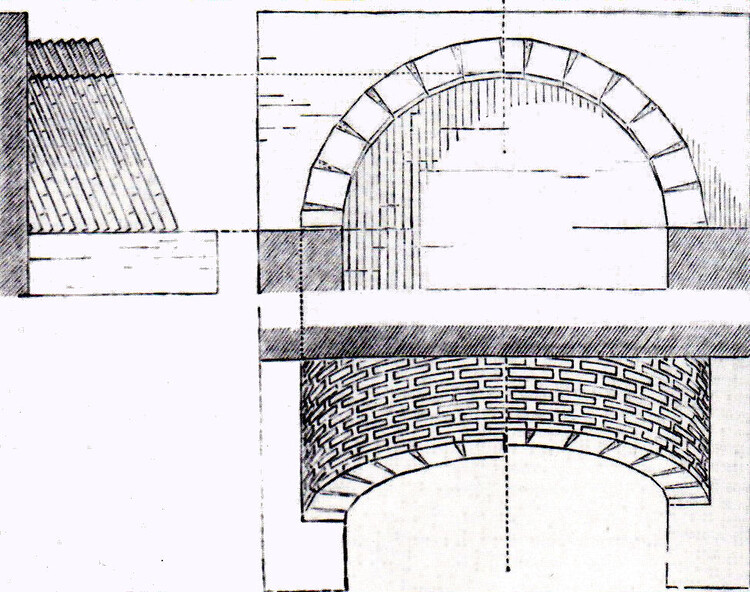

The Nubian vault is a type of masonry construction forming curved structures that act as roofs or ceilings. This is usually barrel-shaped, but it can also be formed into domes. In a land where mud bricks are readily available but timber is not, the Nubian vault's key attribute is its ability to be constructed without formwork. This is achieved by leaning the first bricks against the gable wall. Subsequent bricks are laid leaning against these bricks, and courses corbel out, brick by brick, bonded by mud mortar, until the curved surface is complete.

Unlike the traditional semi-circular barrel vault, the Nubian vault follows the elegant curve of a catenary arch, the natural form assumed by a hanging cable when suspended from two points and then inverted. This gives the vault a rigid shape, which uses less material than a semi-circular vault. Negating the need for timber formwork also conserves trees and forests. Built primarily through the craftsmanship of skilled masons using simple, accessible techniques, the vault employs layers of mud or fired brick that are particularly well-suited to hot climates. The layers of mud or fired bricks are well-suited to hot climates, where the internal temperatures can be up to 7 degrees more comfortable when compared to sheet metal roofing, reducing the building's energy requirements.

This traditional building technique was perhaps first made famous by the twentieth-century Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy. Fathy had lamented the Eurocentric architecture preferred by the rulers of Egypt in the early twentieth century and felt that he had lost a connection to his identity. Known as 'the architect of the poor,' his work can be described as a constant search for the spirit of local culture and the vernacular. He first discovered Nubian architecture on a trip to Aswan in 1941.

His first implementation of mudbrick to form vaults was on the Hamed Said House in Cairo. The ongoing Second World War meant that iron and timber imports had been halted, necessitating local construction methods. This was a chance to finally implement what he termed as 'felt space,' built on local vernacular tradition, and it marked a turning point in his body of work. These principles would go on to be applied at a larger scale in the designs for New Gourna village near Luxor, a relocation project for settlements within archaeological areas.

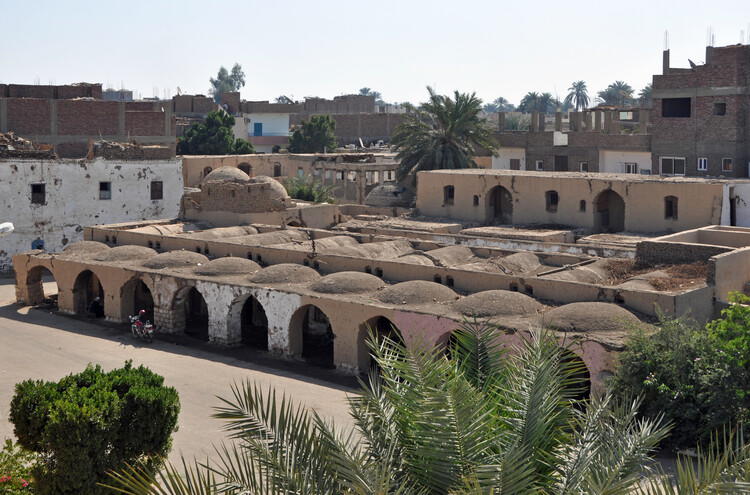

For various reasons, New Gourna did not succeed as a village, and the residents eventually abandoned it. Disillusioned with the lack of support from the government, Fathy left Egypt and worked for a period with Constantinos Doxiadis in Athens, Greece, where he came into contact with the urbanism of the Modern Movement. On returning to Egypt, he was commissioned to design another village in the South, that of New Baris. Unlike New Gourna, which was criticized for being a mimicry of historical building forms, New Baris was a contemporary urban plan where traditional techniques were updated and reinvented. The ends of the Nubian vault can be seen forming repetitive, undulating facades, with the gables removed and replaced with brick lattice work for ventilation.

Due to lack of funding, and the outbreak of the Six Day War in 1967, New Baris was unfinished and remains abandoned. Hassan Fathy would go on to implement his ideas, ironically, in the private houses of the wealthy. The Nubian vault continued to be used in the vernacular architecture of southern Egypt and would inspire the occasional architectural project for its esthetic or cultural value. One scheme has aimed to use its technical, ecological, and social values to improve the built environment and lift people out of poverty in the rural areas of several West African states.

L'association La Voûte Nubienne (AVN, or the Nubian Vault Association) was established in 2000 by French mason Thomas Granier with Seri Youlou in Burkina Faso. Two years before, they had tried to build a Nubian vault at a local traditional arts exhibition. They recognized the need for housing in the Sahel and other dry parts of West Africa. Trees, usually cut down to make traditional timber roofs, were becoming scarcer, while the corrugated metal alternative was both expensive and thermally unsuitable. Thus, AVN was born and now operates in Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Benin.

AVN's purpose was "integrating issues of housing, professional training, economy, environment, and climate." Part of its program is to train individuals in the Nubian vault technique, therefore providing the opportunity for employment as well as creating homes with comfortable internal environments. The success stories did not only include dwellings; one project in Mali was a vegetable storehouse built with a mudbrick vault. Where previously farmers stored produce in corrugated metal sheds and lost the majority of the stock to the heat, using the cooler vaulted storehouse increased their sales and their income.

The Nubian vault, deeply suited to its local environment and climate, is a living tradition that has lasted for centuries. It has been reinvented locally and further afield in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Its simplicity, coupled with its suitability in arid climates, has made it an ideal solution in areas facing population growth, deforestation, and high temperatures. Notwithstanding these credentials, the Nubian vault has a timeless, sculptural beauty, grounded in the earth from which it is made.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Regenerative Design & Rural Ecologies. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.