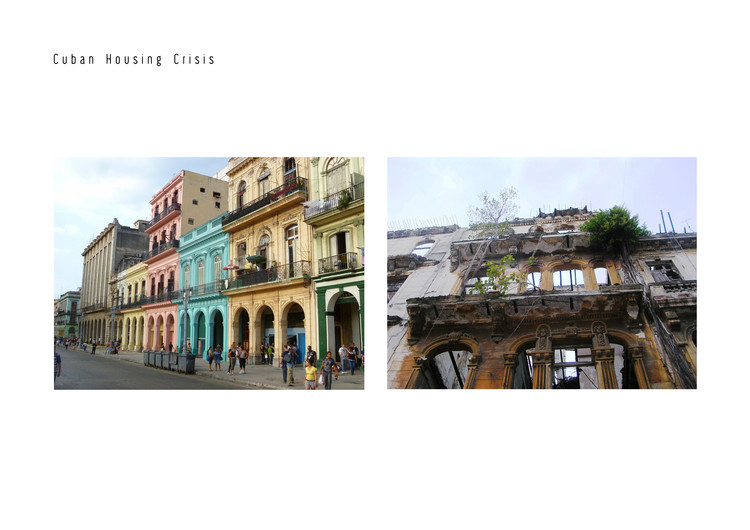

The largest of the Caribbean islands, Cuba is a cultural melting pot of over 11 million people, combining native Taíno and Ciboney people with descendants of Spanish colonists and African slaves. Since the 1959 revolution led by Fidel Castro, the country has been the only stable communist regime in the Western hemisphere, with close ties to the Soviet Union during the Cold War and frosty relationship with its nearby neighbor, the United States, that has only recently begun to thaw. While the architecture in the capital city of Havana reflects the dynamic and rich history of the area, after the revolution Havana lost its priority status and government focus shifted to rural areas, and the buildings of Havana have been left to ruin ever since. Iwo Borkowicz, one of three winners of the 2016 Young Talent Architecture Award, has developed a plan that could bring some vibrancy, and most importantly some sustainability, back to Havana, the historic core of the city.

After half a century of poor maintenance within Havana Vieja, buildings are reported to be partially, or even entirely, collapsing at a rate of 2 every 3 days due to flooding, salt water corrosion, and overloading; as many as 20 families can be living in a villa originally designed for one. Despite a Cuban law preventing people from migrating into the capital, Havana is still struggling with a major housing crisis. According to a 2010 study, the island lacked around 500,000 housing units to adequately fulfil the nation’s needs, but due to the collapsing buildings, this number is currently estimated to be somewhere between 600,000 and 1 million. Havana alone has over 100,000 people without an apartment to live in. In other words, suitable housing is high up on the list of the Cuban people’s needs.

Existing alongside the country’s housing crisis is its rapidly expanding tourism industry. Due to the country’s communist rule, privately owned businesses such as hotels are essentially non-existent, in spite of the nearly 3.5 million tourists expected to visit the country in 2017 - with 90% of them, according to Borkowicz, expected to visit Havana. However, the government has allowed Cuban people to rent out rooms in their own homes since 1997, commonly known in Cuba as "casas particulares," responding to the touristic demand without having to build large hotels alien to the Havana landscape. This concept, as well as the desperate need for housing and possible local economic gain from tourism, is what inspired Borkowicz to develop a proposal to combine social housing with tourism in Havana Vieja.

The idea is to merge the two by renovating existing, partially collapsed buildings around Havana Vieja, and adding vertical extensions to fulfil Borkowicz’s plan to build with an average of 4 floors. Occasionally structures are designed from scratch when the existing building has collapsed beyond repair. As Borkowicz envisions the use of space in a 3:1 ratio of permanent versus temporary inhabitants, these buildings need to not only accommodate for the existing housing shortages in Havana Vieja, but must supersede them. Currently the housing shortages require 9,200 new housing units, with an assumed floor space of 70 square meters per unit. Borkowicz looked at 12 housing blocks already existing in Havana Vieja, using their volumes as a benchmark for calculations on his proposal of an average of 4 storeys per building and concluded that the total generated floor space from his project could amount to 105,812 square meters - 3 times as much space as is currently needed.

Not only will this proposal provide more housing for the Cuban population, it will also serve as a source of income for the inhabitants, as they will be able to rent out more rooms to tourists. One of the main reasons for Cuba’s housing crisis is the lack of financial support, however Borkowicz proposes that residents could repay loans over an estimated 10 year period, while still keeping around 10% of the revenue for personal use (estimated to total around 4 times as much as the average salary in Cuba). For locals, this sum of money can often buy them far more value for money, as some business run two pricing systems - one for locals and one for the foreigners. For example, Borkowicz has noted ice cream selling for 24 times the price when bought by a tourist.

As part of his research project, Borkowicz has established 6 prototypes, each responding to the individual situations on their site: Prototype 1 and 3 take place on existing plots housing single storey buildings in very bad condition that will be completely replaced; Prototype 2 addresses a similar pre-existing condition, but with a building still in good shape that can be built upon; Prototype 4 is an empty corner plot with only partial remains of its previous occupant, making it necessary to design the house from scratch; Prototype 5 connects two parallel streets by joining two existing buildings back-to-back, one on each street. Finally Prototype 6 is not a social housing project, but is suggested to take an empty corner plot and addresses the need for a co-working space that promotes small businesses.

These houses are designed in such a way that the structural support, as well as the sewage or gas infrastructure, can remain entirely unchanged. Instead the transformation of space takes place by rearranging non-load-bearing walls, allowing for flexible floor plans whenever possible so that residents can arrange different combinations of hotel rooms, or alternatively expand their own apartment.

“Casa particulars is not a hotel nor a guest room in somebody’s house but a formula in-between. This significantly changes the way guests and hosts look at each other,” explains Borkowicz in a booklet documenting his research. “Tourists can experience a more in-depth Cuban culture and Cubans won’t feel like simple servants, but partners in an exchange of services and money - but also an exchange of stories, daily routine, and experiences. Both parties will hopefully get a chance to... learn from each other, while at the same time having access to a fully private zone in their rooms or flats.”

This kind of architecture requires a lot of common spaces that both permanent and temporary inhabitants can take advantage of; much more than in an ordinary Cuban apartment or AirBnb. Each of Borkowicz’s prototype buildings is individually designed with respect to the existing situation on the plot, however all five residential plans include an open space with planted areas, often in the form of large inner courtyards. Also included are an open kitchen and living room; a “collective zone” on the roof, including a laundry station and an urban farming space; a zone for tenants to keep chickens, vegetables and herbs; and an “extension” of the space into the surrounding community around the entrance zone.

In his designs, Borkowicz prioritizes natural ventilation, using both the main wide courtyard and smaller secondary courtyards to create cross-ventilation through rooms not directly connected to the street. Open space within the building is above the government’s requirement of 15% of the total area, and the windows and courtyards are protected by permeable solar protection to allow for the passage of wind. In addition to this the design specifies staircases and railings that generate maximum airflow, using traditional Cuban wrought iron elements. The passive cooling system, taking place through underground pipes that suck air through the patios, are stabilized by the constant temperature below ground level of around 15 degrees Celsius.

In addition to the traditional wrought iron railings, Borkowicz’s plan would support the production of Cuban ornamental ceramic tiles, which would be used to cover the roof, reflecting sunlight to prevent overheating. One of the more important choices in Borkowicz’s design is to maintain the existing characteristics of Havana Vieja, with facades that reflect the classical, brightly colored and decorated buildings of the Cuban culture, preserving the tourist appeal of the area. No choice of color is specified, leaving the housing cooperative to personalize each house, hopefully helping them to identify more strongly with the project through the use of shapes, materials and colors that are so abundant within the Cuban culture.

Social, cultural and economic support that can be brought through architectural design is no easy task to accomplish, making the symbiotic relationship that arises from such a project a fantastically beautiful thing to witness. If the predicted deluge of US tourists is to find much more than rubble and homelessness in Havana Vieja, Borkowicz’s proposal is not only beautiful, but desperately needed.

Correction update: This article originally stated that the "casas particulares" system was introduced in 1959. It was actually introduced in 1997.

.jpg?1483017700)

.jpg?1483017590)

.jpg?1483017551)

.jpg?1483017637)

.jpg?1483017747)

.jpg?1483019797)