This article, by David Brussat of The Providence Journal's editorial board, first appeared at providencejournal.com.

In a rating of energy efficiency by the Environmental Protection Administration, New York's venerable Chrysler Building scored 84 out of 100 points; the Empire State Building, 80; but the modernist 7 World Trade Center scored 74 (below the cutoff of 75 for "high efficiency"); the Pan Am Building, 39; Lever House, 20; the Seagram Building, 3. The New York Times reported this story last Dec. 24 under the headline "City's Law Tracking Energy Use Yields Some Surprises."

It was no surprise to Nikos Salingaros and Michael Mehaffy, who have investigated why modern architecture thrives despite its inability to live up to any of its longstanding promises -- aesthetic, social or utilitarian.

Salingaros is a mathematician and architectural theorist at the University of Texas at San Antonio; Mehaffy is an expert in urbanism and complexity in Portland, Ore. They wrote a long essay for the May issue of Metropolis [Mag], "How Modernism Got Square," the third in their series "Toward Resilient Architectures."

Resilience theory, which assesses sustainability in manmade systems, finds that modern architecture suffers an "inherent" inability to "handle shocks to the system." It resists reuse and repurposing. What buildings need is akin to what nature provides: "redundant . . . connectivity, approaches incorporating diversity, work distributed across many scales, and fine-grained adaptivity of design elements."

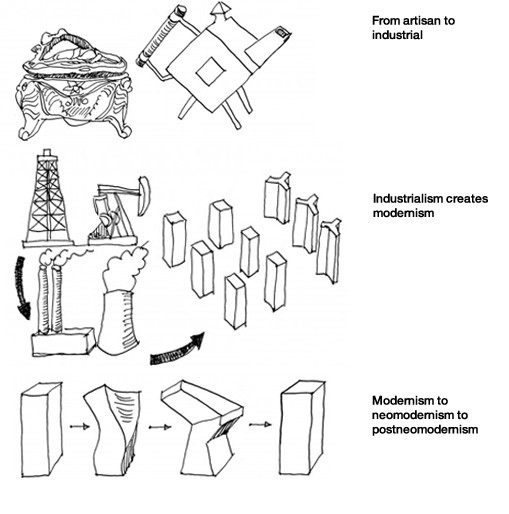

Older structures, they find, have "exactly these qualities of resilient structures to a remarkable degree. . . . Nevertheless, during the last century, in the dawning age of industrial design, the desirable qualities resilient buildings offered were lost. What happened?"

Architecture ousted ornament.

"The fractal mathematics of nature bears a striking resemblance to human ornament," Salingaros and Mehaffy write. "This is not a coincidence. Ornament may be what humans use as a kind of 'glue' to help weave our spaces together. It now appears that the removal of ornament and pattern has far-reaching consequences for the capacity of environmental structures to form coherent, resilient wholes."

This seems highly technical, but the principle is easily grasped. Allow your mind to wander over various parts of your own city. Where do you take visitors to impress them? To old places, of course, not to places built since modernism evicted ornament from architecture.

It's not just a coincidence that tourists, who travel by choice, do not flock to Sao Paolo or Brasilia, or to the outskirts of Paris and Rome. In London, tourists regret new buildings that have invaded old districts and cherish old buildings that have survived bouts of modernization. Likewise even in Manhattan.

One may like or dislike this or that modernist building, but not even modernist architecture critics bother to claim that modernism has produced any lovable cities. And yet the primary purpose of architecture is to design a civic realm that soothes the savage breast. Modernism fails every time. In Providence, for example, Waterplace Park is bearable only because its traditional infrastructure softens the harshness of its more recent modernist buildings.

"Far from being an inevitable product of inexorable historical forces," write Mehaffy and Salingaros, modern architecture "developed as a series of rather peculiar choices by a few influential individuals." They cite Viennese architect Adolf Loos, who wrote "Ornament and Crime" (1908) to market a functionalist agenda. But, they assert, "the machine aesthetic was an artistic metaphor of 'modernity' . . . not a true functional requirement."

A cosmic blunder, to say the least, with profound consequences. Modernism survives its fundamental error because it "paved the way for a dominant theme of modern marketing -- one that can sell almost anything if it's successfully linked to romantic imagery of the future... It was a complete blueprint for remaking the world according to specific concepts of scale, standardization, replication and segregation."

The resulting corporate and governmental gigantism seems less romantic in hindsight. Now more than ever, modernism's brand reflects a new inhumanity of spirit more consonant with Big Brother and the totalitarianism we thought we'd defeated in the 20th Century.

Human society must find a path of retreat. Salingaros and Mehaffy point the way: "We will have to think outside the modernist box to find new forms -- or new uses for very old forms, just as natural evolution does."

[The two prior installments of Mehaffy and Salingaros's series Toward Resilient Architectures, No. 1 ("Biology Lesson") and No. 2 ("Why Green Often Isn't"), are here and here.]

David Brussat is on The Journal's editorial board (dbrussat@providencejournal.com). This column, with more illustrations, is also on his blog Architecture Here and There at providencejournal.com.

Image of Grand Central Station via shutterstock.com