In 2013 former Los Angeles Magazine architecture critic Greg Goldin and journalist Sam Lubell co-wrote and co-curated Never Built Los Angeles. The acclaimed book and accompanying exhibit at the Architecture and Design Museum of LA celebrated hundreds of projects that never quite reached fruition. Following its success, the duo published a second installment: Never Built New York. Having just sold out of its first pressing, the book has garnered similar praise as its predecessor. Goldin and Lubell are currently planning an accompanying exhibit at New York’s Queens Museum that will debut this fall. Fresh off their NYC book tour, I sat down with Mr. Goldin to discuss his latest book and the future of Never Built.

Thomas Musca: You’ve been able to snag two high-profile architects to write the foreword for each book: Thom Mayne for Never Built LA and Daniel Libeskind for Never Built NY. Why do you think they’re so willing to help? Why are they so interested in the unbuilt?

Greg Goldin: I think architects feel that a lot of the work they do is the stuff that we would describe as "on paper." It’s not something that got realized. So, I think that there’s a natural sympathy for this subject matter in general. We didn’t have to convince anyone: "Oh, overcome your worst fears, you’re going to be included in this book that is consigning you to the dung heap of history." I don’t think anybody ever felt that way. I think that they feel like these are things that they don’t want to see just disappear into the archives. There’s a sympathy that already exists. Sam and I knew Thom Mayne and we thought Thom would be good for this and he just said yes. The same is true with Daniel Libeskind. Our editor, Diana Murphy, is friends with him. We felt fortunate because he has an amazingly positive attitude for a guy who’s been batted about by how things work in the real world of trying to get stuff built. You can have the dream project, Freedom Tower, and get ground down by it. But Daniel, bless his heart, is kind of upbeat about the whole thing, and that comes across in what he had to say in the foreword.

TM: You’ve focused on two American cities in which the bulk of unbuilt content comes from the 20th century. Would a “Never Built Rome,” with centuries of history to consider, be too grandiose a project?

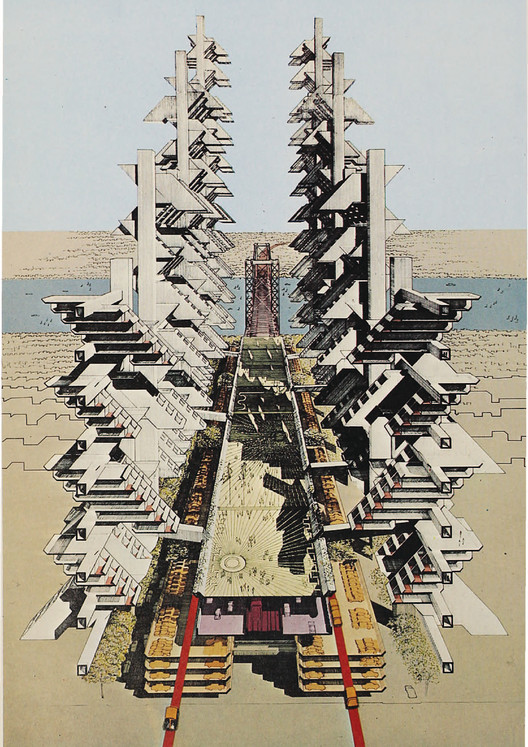

GG: If it’s an interesting project, we don’t care what epoch it comes from. That can be weighed in different ways. It can be purely an aesthetic proposition, but it can also be a proposition that in some way pointed toward a different kind of future or ideas about the future that people were grappling with, let’s say after the French Revolution. There’s a lot of great material immediately after the revolution, just like after the Russian Revolution. There are all of these propositions for “what should the built world look like?” and, of course, none of them were realized. So yeah, that can be 200 years old, that can be 100 years old. We’re coming up on the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, and we’re almost 240 years on from the French Revolution. I think it’s true for Rome. If we found drawings of something from the Renaissance, why not? I don’t think it’s excluded by age, let’s put it that way. But then you do have to look at it and say “well, does it have meaning for how we relate to the city now?” If it’s just a bauble I supposed we’d be less inclined, but if it’s an entertaining enough bauble we might still go for it.

TM: How serious does a project need to be to qualify for consideration in the book?

GG: The criteria that we’ve developed is: it has to have been a proposition that had some kind of backing, that did have some prospect of actually being built, whether that was because a developer was attached to it or there was a realistic building site available for it. Sometimes we chose a few things because they were competition entries that, as frequently happens with architectural competitions, not just in the 20th and 21st centuries but also in the 19th century, the losers often are more interesting than the winners. That’s not always the case. Central Park is probably the biggest exception to that, but in other instances you go "wow, how come Rem Koolhaas didn’t win this or Zaha Hadid, and instead it’s a Norman Foster thing that nobody really likes"—to name names. So, we feel like there has to be something fairly realistic about the possibilities.

TM: Would Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mile High Tower be considered serious enough or is that too much of a vision?

GG: That’s very tough, because clearly it is just a vision. On the other hand, it pointed the way for skyscrapers that continue to get—if you’re in Qatar—taller and taller and taller, or as an aspiration. So, then the question is what is the nature of the Frank Lloyd Wright proposal, not just in terms of its height, but what was he really proposing? To give you a smaller example of that, there were these skyscrapers that he wanted to build called St. Marks in the Bowery. What’s interesting about them is how he treats the skyscraper, and not so much how tall they are. I think it can kind of cut both ways. There are NYC proposals to burrow into the ground a mile deep, but they can be interesting because they point you towards a set of ideas that have currency and may still be, if not essential, not so unrealistic, or not so much of a dream that they belong in a Marvel comic strip.

TM: So, continuing off the idea of the Middle East here, a “Never Built Dubai” would almost exclusively take place in the 21st Century. Because of the overly enthusiastic ambitions of oil sheiks, the city has racked up a large number of canceled projects in recent years. Is a decade and a half a long enough time frame to pull from?

GG: No. I don’t think so. If you look at Dubai, that’s just the influx of radical amounts of money in a compressed period of time. I think that if the oil spigot were turned off, that place would blow away and revert to what it always was. I don’t think it’s a model for any city in particular. Now, perhaps I’m wrong because I don’t know every one of those projects intimately, but I think as a rule you could describe them as vanity. I don’t think that they are a model for either where cities are going, or even how cities should be built. I think you have to apply some sort of test to see that it could actually be a city before Sam and I would put that between binders.

TM: Are there any egregiously bad projects in the book that New York’s better off without?

GG: There’s two that come to mind. The first is one of the losing propositions for Central Park by John Rink. I describe it as kind of paisley. It’s this totally sort of ordered but unhinged sequence of French Gardens—completely formal and symmetrical that would have never been...

TM: ...appropriate.

GG: Yes, and it’s just the pendular opposite of the Central Park which is the clearing in the distance. The other one that comes to mind is approximately 100 years later, a Marcel Breuer tower that would have driven enormous piles right through Grand Central Terminal and would have hovered over it like one of the spaceships from the Martian Chronicles, except that it was a thoroughly modern building in the mold of the Pan-America building. So, you would’ve had this Bauhaus-ish thing hovering over this vaguely neo-classical remnant of Grand Central, and it would’ve been a hideous mashup. I think New York would’ve regretted that as much as it ever regretted tearing down Penn Station.

TM: Do you have a sense of the kind of space you’ll be using in the Queens Museum? Is it too early to ask about what elements you intend to include?

GG: We’re pretty much on track. We’ve developed a fairly clear sense of the exhibition. The big moment in the Queens museum is what’s known as the “Panorama of New York City.” The panorama is actually a model of all of New York City built for the 1964 World’s Fair and it’s housed in part of the museum that’s just a huge hangar space—you could probably park a 747 in there. What they are letting us do is insert our own Never Built projects into the model itself. The model is a scale of 1:1200, so it’s big enough so that you can actually see stuff, but it’s small enough that it’s going to be tricky to do what we want to do. What we’re hoping to do with the space is give people a kind of other-worldly feeling. We’re not trying to give you all the particulars of 150 potential Never Builts for all the Boroughs of New York. We’re going to build these models that’ll get inserted into the panorama, and they’re just going to be to scale massing models illuminated from within and made of frosted plexiglass, so you’ll see these objects scattered about. We are also working with a lighting designer to transform this room, which really has the feeling of an airplane hangar, into a more conditioned space where visitors can experience a simulated sun cycle over New York’s five boroughs.

There’s also a catwalk that surrounds this whole thing; what we’re planning to do there is to use these virtual reality viewers called “Owlized” pointed at specific spots within the panorama, and those individual projects will come to life. So what you’ll be seeing is New York as it presently is and then, through animation, the Never Built will morph into a different kind of presentation, it might be an interior or an exterior, or a flyover, all different ways of seeing an individual Never Built. So you might be looking at Grand Central Terminal and out of that will emerge IM Pei’s proposal from the early 1950’s to tear down the train station and build this incredible hyperbolic tower. There’s also a gallery next to the panorama that’s super tall and narrow that will hold a more conventional combination of architectural models, original drawings, and reproductions. We’re hoping to make that space as kinetic and dynamic as possible, where you’ll just be moving through a kind of cacophony of the never built. Then there’s one more space that is completely different and difficult to work with. It’s a sunken area that used to be an ice rink where we can’t put up any original artwork because of the light flooding in from the skylights. Our proposal for the space is to actually have a bouncy castle made just for kids and it’ll be for an Eliot Noyes Never Built that would’ve been for the 1964 World’s Fair.

"Never Built New York" Explores the Forgotten Past and the Future that Never Was

Read a review of the book here.

TM: Never Built Los Angeles was simultaneously developed as a book and physical exhibition, whereas Never Built New York’s Exhibition is coming several months (Fall 2017) after the book. How did the research processes for the two projects differ?

GG: With Never Built Los Angeles, the Getty approached the A+D (The Architecture and Design Museum of Los Angeles) and said we have these four models of unbuilt projects, would you guys be interested in putting them on display. That was the whole package, that was the overture, there was nothing more to it than that. Tibbie Dunbar, the director of the museum asked Sam Lubell and I if were we interested in curating a show around these four models. When we looked at it we said yes, but that’s not really the subject of an exhibition, that’s just kinda putting some models on display. And that led to a huge research project for an exhibition, which in turn gave us the idea to do a companion book. So, with LA, the exhibition came first, then the book derived from the research we were doing for the exhibition. With New York we realized that there’s sort of a franchise here maybe, and our publisher wanted us to do a book. As a result, the Never Built New York book will have been out for almost a year before the exhibition. In many ways, while the show is informed by the projects in the book, the exhibition’s going to have its own life independent of the book. The book is no way a catalog for the exhibition; they’re just complimentary.

TM: Is Never Built now officially a series? Do you and Sam plan on adding a third city?

GG: We do—we are looking at Paris. France, not Texas.

Never Built New York

Find out more about the book here.

Thomas Musca is the assistant curator for the Queens Museum’s upcoming exhibition Never Built: New York, and the Architecture and Design Museum’s 2013 exhibition Never Built: Los Angeles. He is currently studying architecture at Cornell University and is a contributor to ArchDaily and Metropolis Magazine.