The current state of architectural design incorporates many contemporary ideas of what defines unique geometry. With the advent of strong computer software at the early 21st century, an expected level of experimentation has overtaken our profession and our academic realms to explore purposeful architecture through various techniques, delivering meaningful buildings that each exhibit a message of cultural relevancy.

These new movements are not distinct stylistic trends, but modes of approaching concept design. They often combine with each other, or with stylistic movements, to create complete designs. Outlined within this essay are five movements, each with varying degrees of success creating purposeful buildings: Diagramism, Neo-Brutalism, Revitism, Scriptism, and Subdivisionism.

It is understood that there are many other concurrent architectural movements not mentioned here, most of those attributable as stylistic in nature. Such movements contain either a decorative, minimalist, or sculptural approach to design, where design is applied manually through aesthetic decisions. Such styles do not have as their identifying focus to create an architecture that is more responsive or adaptive to the users, site, context, environment, etc.

PART ONE: GEOMETRIC SHAPE

Diagramism

In the last decade, architects have acquired the ability to create virtually any form via software advancements, yet they still yearn to create meaning with their designs. These two forces have combined to create Diagramism. Architects seeking purposeful designs through this movement take: (1) big ideas derived from the particular strengths, constraints, and attributes of a particular project, such as vehicular circulation or view corridors; (2) create diagrams to show how a potential design can take advantage of this condition; and then (3) literally use the diagram to form a 3-dimensional shape. BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) is the leading firm in this movement, as well as MVRDV and Qingyun Ma’s MADA s.p.a.m.

The ideas are so strong that projects can be iconized. Diagrams are usually black and white or of one color, representing the guiding principles for the form of the resulting building. BIG’s homepage plays homage to this idea of simplified purposeful form, as each project’s strongest idea manifests as a project icon.

There is a considered process of editing, or paring, which results in the pure ideas. The ideas that are focused are not usually abstract or poetic in nature, they are pragmatic. A ski slope on top of a waste-to-energy plant is exactly that. A courtyard apartment building that maximizes outdoor terraces is literally angled towards the view, almost pyramidal. The facility of the design idea is so evident in the resulting form, that the building as a whole expresses meaning and purpose. Ideas can filter down (or up) to multiple scales, further giving meaning to the components of a structure. It can simplify design decision making by having consistent rules and purpose within the design.

Behind the scenes, these Architects are conducting many simultaneous or sequential diagrams, relating to ideas of context, environment, economics, zoning, etc. Circulation diagrams are often used to establish building forms. It is up to the designer to create the hierarchy of the contributing forces to result in the purposeful building design. The resulting form itself becomes operative to the architect’s goals.

The notion to express a building’s purpose is not necessarily new. But, as mentioned, our ability to easily represent these ideas figuratively is recent. It is possible Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York is an early example of Diagramism: the building’s spiraling form is expressing the function of the continuous ramp, which rests on a orthogonal podium base helping to define the resulting form within its context. As for previous design movements, Diagramism often differs considerably from Functionalism, where the static idea of program defines a form rather than Diagramism’s focus on experiential and dynamic forces that a building’s form may solve.

Neo-Brutalism

An ideological cousin of Diagramism, Neo-Brutalism also has strong diagrammatic geometries represented in form. The champions of this movement were educated and matured when Brutalism was king in academia during the 70’s, such as Norman Foster, Santiago Calatrava, and Renzo Piano. Defining Brutalism is not within the scope of this essay, but a summary is as follows. Architects and Planners felt omnipotent to solve people’s behavior. Instead of examining existing modes of behavior and movement, and allowing a design to result after such human analysis, Architects attempted to forecast culture. Modularity was employed with pure geometric forms, and buildings were conceived as behavioral devices.

What Neo-Brutalism does singularly different from original Brutalism, is to employ the use of glass and steel instead of concrete. By gradually changing the palette of materials, this technique professes a more open architecture. But, architecture is understood to be about movement and use of space, not just transparency of material. Prescribed layouts that do not allow for adaptability or resultant geometries, owe much more to their cousins of 40 years ago than their savvy use of modern technology and equipment would lead you to believe.

Thus, what distinguishes Diagramism from Neo-Brutalism is whether the idea of purpose transcends from research into the project, ie whether the design is “resultant.” If a geometry is forced upon the project or is too heavy handed, it is considered brutal. Incidentally, Brutalist forms are generally simpler, more pure shapes, re-emphasizing the notion that the geometry is imposed upon the users. Besides Norman Foster’s recent Yale School of Management building, pictured, another example might be Apple’s new campus’ unforgiving “ring.” An open analysis of Apple’s program might develop an understanding of ingenuity, difference, and innovative thought. However, the building more purely shows the top down theory of forcing constraints. A circle is a locked geometry.

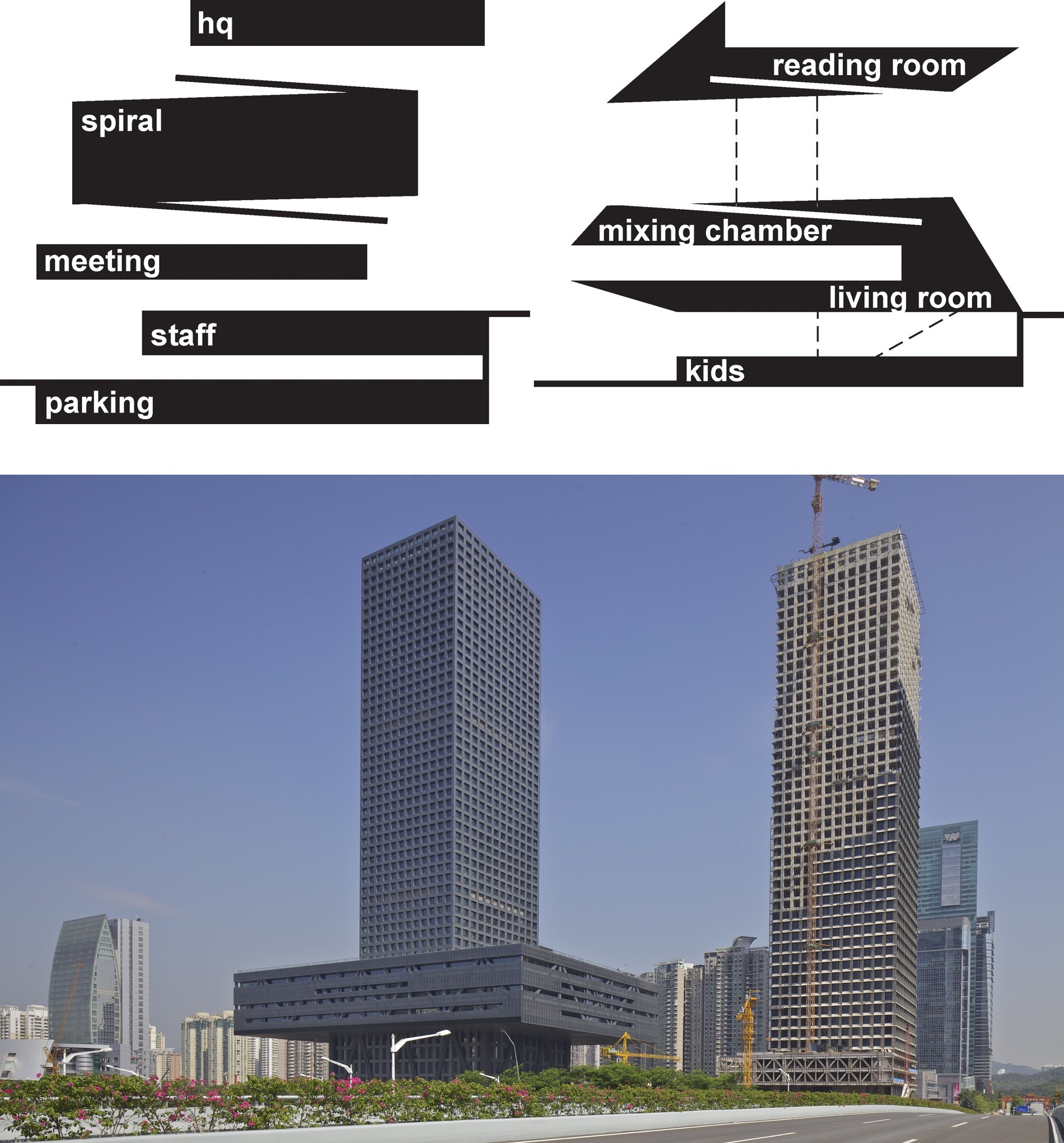

OMA is a firm that employs a fluid use of both Diagramism and Neo-Brutalism, switching seamlessly between resultant geometries and unresponsive forms. At the moments when OMA’s work tends towards Diagramism, an adaptive result might be the Seattle Library, where distinct programmatic pieces are stacked in a sequential array. Also more diagrammist would be the IIT Student Center, where the form literally results from an investigation into the acoustic control of the elevated train’s noise. Of the instances where OMA tends toward Neo-Brutalism, a recent example might be the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, but much of their earlier work also contains what could be considered to be oppressive geometric forms.

PART TWO: COMPUTATION

The final three movements are typically encapsulated by the term Parametricism. But, Parametricism is not so much an architectural movement as it is a computational concept. The computer is now able to link components of our designs so that the geometries created are technologically intelligent. That does not necessarily mean the resulting form is intelligent. Many buildings which are drawn via parametric software do not inherently have purpose, and are really accidents of their fatherly software. However there are many ways in which architects are adding intelligence into the built world utilizing these tools, and those are listed here.

Revitism

First, the least benevolent parametric architecture. I don’t believe anyone has yet to define the design movement which characterizes the majority of current commercial construction. It is the result of the software designing the building, in which most of the design decisions are made haphazardly in the second half of drawing production. More important than the art of creating the building, the new process of creating the “Revit Model,” has become the main operation. Project managers, or BIM Managers, are now managers of software implementation rather than creators of the built world. This is an important distinction: never before has the production of construction documents been about the documents themselves. The largest Architecture firms, such as Perkins and Will, HOK, and Cannon Design, are typically guilty of this design “technique.”

After typically quick stages of concept design, projects are rushed into Revit during Design Development. Managers spend the majority of their time determining the hierarchical tree of component “groups” and “families.” Drafting has become transfixed on how to code these elements. A draftsperson may spend so much time on designing the elements and sub-elements of a component, that they can miss entire relationships to the whole building. A surface which would be elegant and purposeful in concept design, gets repurposed as a “curtain wall” or as “cement fiber board.” Too often, picking the width or detail of a window system mullion becomes a multiple choice of existing manufacturer details, not a discussion of that detail’s impact on overall concepts. Much meaning is lost in this translation, often bypassing design intent as a ruling principle. What results are buildings where you can clearly see the components and their intellectual separation from each other.

Examples of Revitism are pervasive in our environment, including most hospital and education buildings constructed in the last decade. Often contemporary buildings are purely Revitist, having no purpose other than the materiality of the component. Though program will certainly reside within the resulting edifice, the general form of the building is ignorant, and does not respond to natural human occupation, movement, or comfort. This elemental design movement is so pervasive it has become its own aesthetic style, where the collage of material application is the contributing design principle - whether or not it is produced parametrically.

Scriptism

Also known as "computational design," there are vast amounts of research and publication in this realm. Scriptism incorporates what is typically considered algorithmic modelling, specifically through software such as Grasshopper or its kin. Variated surfaces, component design with influencers, etc, are types of Scriptist operations. These various uses are frequently purposeful, and can create architecture that is responsive to such stimuli as sunlight, wind, views, program, context, etc.

We must be careful about when to assume whether a Scriptist model is purposeful. Some good examples of resultant analyses include studying biological forces or using statistics to generate a geometry. With time and further research, designers can maximize the potential of these discoveries. While these explorations remain mostly academic, relegated to the smaller scales of construction such as installations or building facades, the ability to translate this research into an effective building is promising.

Another potential for Scriptism is to add multiple levels of details that architects have otherwise been too timid to employ. Many theorists devise that we both live within and interpret a fractal world, and an ideal built environment should mimic the patterns of the natural world. Software has a unique ability to both measure and deploy fractal geometries to make buildings that are more legible, responsive, relatable, and comfortable. This would be a return to a historic conception of architectural texture. Scriptism is unique in its ability link these multiple scales of design in a coherent and harmonious manner, creating an orchestrated hierarchy.

Subdivisionism

Subdivisionism is a category of design frequently described as either "rounded," curvaceous, or aerodynamic. Most examples of this type of architecture are well-intentioned, and utilize an analytical knowledge of circulation, environment, or program, to produce responsive geometries - frequently combining with Diagramist principles.

Often these geometries reference movement, and create futuristic shapes that are fluid and elegant. Zaha Hadid is one of the most renowned designers in this realm. A similar approach to design can be seen in the work of architects like Jurgen Mayer H and firms such as UNStudio and MAD Architects.

The name Subdivision comes from the modelling technique. A brief summary for those who have not used Maya or similar software: (1) All 3-dimensional forms are defined by vertices. For example, a simple cube is defined by 8 points (vertices), in the X, Y, and Z directions. (2) Each of these surfaces can be further divided, or subdivided. Let's say we added 4 more vertices to create a new plane in between two surfaces of the existing cube. Now there are two seamless connected cubes. (3) Each vertex can be manipulated in any of the 3 axes, creating complex geometries and complex surfaces that are both concave and convex. (4) The software will calculate the new complex form and visually represent it as either curved or triangulated. (This is an oversimplified explanation, but that’s the gist).

The software itself is borrowed from the fields of animation and industrial design. A variation of this type of modelling with a similar outcome can be conducted with NURBS in the program Rhinoceros where control points "affect" the curve of a line, and multiple curved lines are joined together to define an undulating surface. The construction industry now has digitized factories that can create full size versions of these triangulated or double-curved surfaces and components, using 3 or 5 axis mills, along with other techniques. The advent of 3D printing will certainly contribute to the possibilities for Subdivisionism.

The resulting forms are sinuous, and allow shapes to blend into one another. Sometimes the curvaceous forms are simpler, employing the simpler techniques of either “extrusion” or “fillet.” But, as long as these shapes contain purposeful geometries, the resulting building will be visibly useful and navigable.

Parametric Posers - Designs Masquerading as Intelligent

Copycat architects see the amazing forms enabled by the movements listed in this essay, but are not focused on deploying their use through analysis. These are designs that utilize some of the discussed visual languages with no overarching purpose. As architects, we need to be aware that all appearances are not equal. Simply because architects can angle a roof or curve a wall, does not inherently mean we should. It often leads to uncomfortable, discordant geometries.

CONCLUSION

The most important goals for a project should always be the starting point for a design investigation. The architectural design movements discussed - hybridized or separate - all relate to creating a more intelligent built world. A purposeful architecture should integrate a flexibility of program, an accommodation of the environment, and a contextualization within the urban fabric. Buildings should be relatable to the average inhabitant, be cohesive with ideas, and be inherently performative.

Let us not judge a building on its uniqueness, or departure from the past, though these may be good qualities. Let us evaluate a building on its efficacy of form and material usage in reference to context and human occupation; a more purposeful architecture.

Michael Wacht is Principal of IntuArch, a Los Angeles architecture firm established to create effective designs that result from cultivating the most important goals of a project. Prior to founding his own firm, he was Director of the Los Angeles studio for Shanghai based MADA s.p.a.m., apprenticing under Qingyun Ma, Dean of the USC School of Architecture. Visit IntuArch at their website, or follow Michael on twitter @intuarch.