The following are excerpts from one of 41 interviews that student researchers at the Strelka Institute are publishing as part of the Future Urbanism Project. In this interview, James Schrader speaks with Adam Snow Frampton, the co-author of Cities Without Ground and the Principal of Only If, a New York City-based practice for architecture and urbanism. They discuss his work with OMA, the difference between Western and Asian cities, his experiences opening a new firm in New York, and the future of design on an urban scale.

James Schrader: Before we get to future urbanism, I thought it would be interesting to look a bit into your past. Could you tell me about where your interest in cities came from? Were there any formative moments that led to your fascination with cities?

Adam Snow Frampton: I was always interested in cities, but not necessarily exposed to much planning at school. When I went to work at OMA Rotterdam, I was engaged in a lot of large-scale projects, mostly in the Middle East and increasingly in Asia, where there was an opportunity to plan cities at a bigger scale. In the Netherlands, there’s not necessarily more construction than in the US, but there is a tradition of thinking big and a tendency to plan. For instance, many Dutch design offices like OMA, West 8, and MVRDV have done master plans for the whole country.

JS: It seems like urban planners do not have the power to really influence much in the US. Do you think that, because of these limitations, architects and urbanists in the US don’t think big, the way that, say, the Dutch might?

ASF: I think there is a will in the US to make cities better and work better, and it’s not easy to pinpoint and say that it fails due to the fault of one actor or another; it’s a combination of very market-based planning and development policies that are not influenced by designers, but also designers themselves who are not taking on a role that would allow for a genuine transformation of the city. After I moved to Hong Kong a little over four years ago, I led some competitions on behalf of OMA. For instance, we were asked to rethink a very big part of Shenzhen, which was amazing because even though we only had the opportunity to deal with it very superficially, we were really thinking about not only where development happens but also how the whole transportation infrastructure would work. The approach was to address urban scale issues in a very graphic way. At OMA, there’s always this process of superimposing patterns and other cities onto a site as an initial gesture. For me, that was liberating because I saw that there could be an artistic dimension to planning. Of course that’s not the only reason I became interested in cities, but I think it is very powerful because it is part of what architects are trained in, and it can become a tool for dealing with all the other dimensions of planning.

JS: What about living in Rotterdam and Hong Kong? Did that have an impact on you?

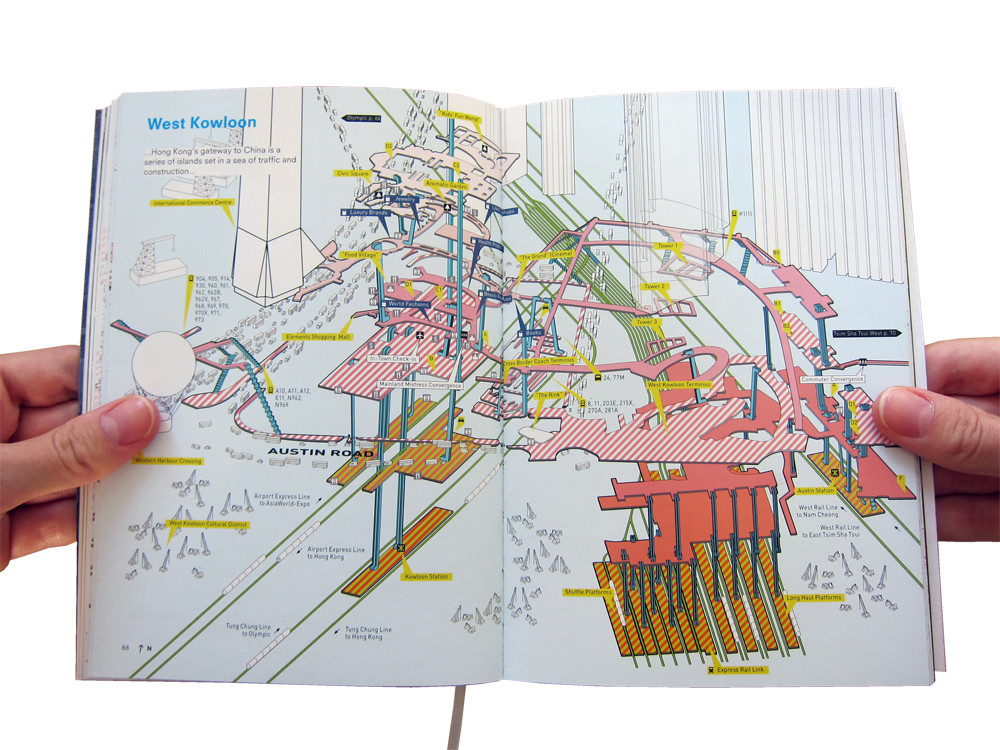

ASF: Yes. I think in Hong Kong more so. In Hong Kong, it’s just a radically different city than most other places. I think it’s also extremely vibrant and functional. In Hong Kong, there’s something like a 90% public transportation share for commuting to work, which is the highest in the world. Living there and experiencing it caused me to see it as a potential template for other places in the future. One thing that really fascinated me is how living in the city and moving around it is a totally three-dimensional experience. Together with two other architects, Jonathan Solomon and Clara Wong, we mapped these spaces, looking at the continuity of public space through pedestrian overpasses, office lobbies, shopping malls, and MTR platforms, etc., which eventually became the book Cities Without Ground.

JS: I’m curious about how the urban study of Cities Without Ground began. Was there a client or a brief you were responding to? Or did it come about based on your and your collaborators’ desire to describe the city you were experiencing in your daily lives?

ASF: At the time, Jonathan was teaching at Hong Kong University and led a seminar called ‘Learning from Louis Vuitton’. Jonathan was working with Clara making three-dimensional maps, initially focused on shopping malls. When the three of us began to work together, our overlapping interests became really productive. There was support through Hong Kong University, but we mostly it was self-initiated. The project was a process of discovering things that, in retrospect, are really obvious characteristics of the city, but no one had really mapped them before. And then we went to a publisher, ORO Editions.

JS: It’s interesting that it began as a study that focused mostly on shopping malls and then grew into a whole theory of the city. Was it intentionally positioned as a response to other canonical books on cities, like Delirious New York or Reyner Banham’s book on Los Angeles?

ASF: At various points, we looked at all these manifestos on different cities, like Delirious New York or even Made in Tokyo. We thought that our project was so limited in scope, and we wondered how we could make this into a bigger manifesto. In the end, we saw that even though it is specifically about Hong Kong, it is applicable in a broader context. For instance, in Mainland China, Hong Kong is already seen as an urban model. And now, through my own practice, I’m involved in a master plan and architectural competition for Shenzhen. We’re planning about one million square meters, so it is, in a way, a new city. And they’re looking for layered public space in a way that is modeled after Hong Kong, where there’s multiple levels of ground or public interaction.

JS: To what extent can the Hong Kong model be exported? Is Hong Kong’s unique urbanism and extreme density due to its specific location, wedged between the mountains and water? Across the harbor in Kowloon, it’s flatter and the space is less constricted, but it still has much of the dense, layered urbanism found on Hong Kong Island. So maybe whatever incubated on Hong Kong Island, in those unique conditions, can still be exported to other locations that don’t have those constraints?

ASF: Hong Kong is definitely unique. But I think it’s also necessary, if you want to plan a massive city without cars, to consider something similar to Hong Kong. We saw lots of related systems in other places. For example, in Minneapolis, due to its cold climate, there’s a system of elevated skywalks. In Shinjuku in Tokyo, London, or in New York around Grand Central, you have extensive networks of underground pedestrian connections around major transit infrastructure. In other cities, there’s always a reference to a stable or fixed ground. What’s specific about Hong Kong is that, sometimes you’re in a tunnel that turns into a bridge, or you’re in a building, like the Hopewell Centre, that has one lobby on the first floor and another lobby on the nineteenth floor, because of the radical topography that the building is embedded within. That, I think, is the specific part about Hong Kong. On the other hand, multiple levels of transit, retail, parking, or open-space could happen anywhere. Already, in Asia, people are thinking a lot about how to emulate some of the patterns you see in Hong Kong, simply because it’s not viable for everyone to follow the American model of having a car and driving from work to home.

JS: In a lot of Western cities, the skywalk systems of the 1960s and 1970s were, a few decades later, largely derided as failures that killed the life of the street below. In Asian cities, however, it’s so dense that a layering approach actually works.

ASF: In this competition that we’re doing in Shenzhen, the brief already stipulates that they want public levels at 0 meters, 12 meters, 24 meters, and 50 meters. I was totally shocked because that’s pretty radical. Yet, when we went to Shenzhen, we saw a number of developments that are already under construction or nearly finished which already incorporate this principle.

JS: Will Cities Without Ground impact and fuel your future design work?

ASF: Yes, I hope so. But I’m not sure if there will be a direct link from the book to my work. That was always the question when we were making it. Obviously, the term ‘guide book’ that we use is a bit of a misnomer. It is more like a manifesto. But the forms of the city are so complex and specific that it’s hard to take that and just do it somewhere else. But I do think that some of the thinking in there will sublimate into my own design work in the future.

JS: I’m curious why you feel now is the right time to launch your firm Only If. What was the impetus to, at this moment, break away from OMA, move to New York, and take that leap?

ASF: After seven years at OMA, I learned a lot, but now I’m ready for something different. I am also coming in to New York at a moment when people are starting to rethink the city. I’m trying to maintain the links to Asia and to keep working there, but by virtue of being here, I’m trying to import some of what I learned abroad. New York has transformed over the past ten years, for better or for worse. Now, a lot of the housing stock is becoming obsolete, or is at risk for flooding. There’s a huge amount of development going on in New York. After Hurricane Sandy, perhaps there’s a mood for thinking bigger.

JS: Is it hard as a young, small firm to get urban-scale projects?

ASF: Our work now is ranging from very small, about 150 square meters, to a million square meters, or even bigger. We have three urban-scale projects right now. One is our entry for the Shenzhen Biennale, which is New York envisioned with the density and urban conditions of Hong Kong. It’s very speculative. When we projected the density of Kowloon onto Manhattan, we discovered that it would allow the city to occupy a much denser footprint, which also coincides with the flood boundaries that are due to climate change. So we re-envisioned how to achieve that kind of density and what emerged was a series of new city centers on top of the existing infrastructure, like you have in Hong Kong. This also produced a much higher contrast between the urban and natural fabric, like Hong Kong.

JS: So it’s not about allowing for an increased population but rather about reconfiguring the population that is already there?

ASF: Yes, exactly. But that density could also accommodate a higher population. The second project is a master plan in Shenzhen, which we are now in the second phase of the competition for, together with two other offices in China. We’re wrapping that up in December 2013. We’re also doing planning work here in the US, in New Jersey. It’s a master plan that’s about 130 acres in a less urban context. I think it is actually not that hard to find work in the US at this scale – there are very few young offices doing planning.

JS: Right, because it seems that many young firms in New York are primarily doing interior renovations of condos. But maybe that’s as much about interest as it is about limited opportunities.

ASF: Everyone does restaurant and apartment interiors in New York when they’re starting out. I wanted to avoid that as a primary focus in the office because, although it’s nice to do that kind of work, it’s also very limiting.

JS: I was reading through your firm's statement on your website and it ends with: “our cities, environment, and way of life can be reimagined only if architecture is present,” which I suppose is where your firm name comes from. I’m curious what you see as the role of architects and urbanists in the contemporary world or future world. It seems that so much of what gets built is dominated by politics, corporations, or real estate development. What impact can architects have?

ASF: Architects and urbanists nowadays have less of a share in the production of cities and buildings. That has a lot to do with the increasing complexity of projects. It used to be, ten years ago, that architects had a responsibility to produce a certain amount of drawings. But now, for instance, you have facade consultants, which is a relatively new profession, because all of a sudden curtain walls have become extremely complex and architects can no longer handle it. And drawing sets themselves are much longer because there’s more and more technology inside the buildings. In buildings themselves, we have less and less control over what happens. You can also say, in how cities get made, there are fewer and fewer architects and designers involved. It’s happening faster and happening with less design. So there’s definitely reason to be cynical about it. But I think that there are also a lot of reasons to be optimistic. I think there’s more and more interest in what good design can yield and how it can generate value and efficiency.

JS: Do you think architects should take on some of the responsibilities that they have lost, or maybe even partner with real estate developers more, or get into policymaking? Or are those just potential distractions?

ASF: I think, for me, the key is focusing on our own disciplinary knowledge and tools. So many projects are done in which designers claim an expertise about some other discipline. And of course, to make something new you have to bring something from the outside. If we, as designers, focus on what we know, that’s a good position to put forward designs and ideas that we can back up.

JS: Do you have any general predictions, based on your experience, about what cities will be like in the future? Or what trajectory New York, Hong Kong, and Rotterdam are going in?

ASF: It’s hard to say. Those are all very different places, of course. It’s well known that a lot of people are predicting that the forces of globalization will make everywhere more uniform, that every city in the world is going to become more and more similar. That’s true to a certain extent. In Hong Kong, those forces of globalization exist as much as everywhere else, and the city is a product of it, but you also have a local, unique, culture as well. That was actually one conclusion from our book. So, extrapolating from that conclusion, I think one thing you could say is that you might actually find cities that are more and more different all over the world. I’m not sure if that’s really a prediction – maybe that’s just my hope.

Trained as an architect, James Schrader is currently at the Strelka Institute in Moscow researching how the nodal structure of the Metro system is reorganizing the city. He has previously worked in diverse global contexts, most notably on regional planning research for the Shrinking Cities Project in Berlin, a facade installation for the Shenzhen Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, and master plans for new districts in Los Angeles, New York, and Kuala Lumpur.

Learn more about Only If at their website or on their Facebook page.